[Originally published as Beavers That Build Burrows Instead of Dams]

Beavers are renowned for their incredible ability to build wooden homes for themselves, called lodges. And everyone knows how they alter their environment with the construction of dams. But not all beavers were master engineers of aqueous, wooden architecture. One extinct beaver, Palaeocastor, lived far away from water. Instead, it made its home by excavating spiral-shaped burrows in the middle of dry grasslands!

The following article is a summary of the research pertaining to “Paleocastor Burrows as Post-Flood Biostratigraphic Markers” by Chad Arment.

Devil’s Corkscrews

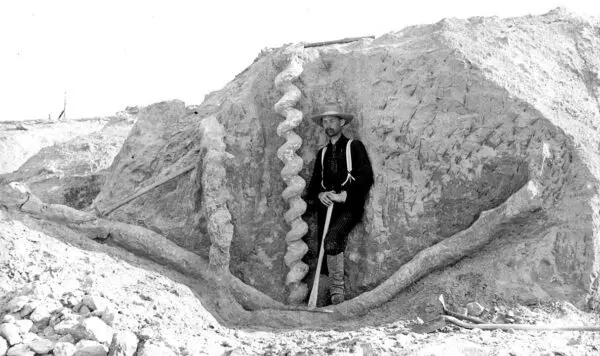

In 1891, Dr. Erwin Henckley Barbour examined strange, spiral-shaped discoveries all across the badlands of western Nebraska and eastern Wyoming.1,2 Ending in a sloping, horizontal tube, these peculiar structures commonly approached nine feet in depth and looped 14 feet in length! And they weren’t rare either. Barbour reported that the unusual structures often occurred in groups covering an area of several square miles, with some covering an area of four or five hundred square miles.3

The local ranchers had many names for them — “screws,” “twisters,” “Devil’s corkscrews” — but these anomalies puzzled scientists. Just what were these ridiculous-looking shapes? Some scientists thought they might be fossilized plant roots or burrows. Others suggested they were concretions or fossilized bryozoans, small filter-feeding animals that live in colonies. Maybe ancient worms left them behind.

In time, scientists discovered the creator of these marvels hidden inside its own creation: the fossil of an extinct, small rodent. These corkscrew-shaped structures were burrows that became filled in with sediment. Palaeocastor, meaning “ancient beaver,” was the name given to the creator of these burrows.

A Burrowing Beaver?

Extant beavers are large, semi-aquatic rodents with webbed hind feet and a flat, broad tail. Beavers live throughout North America and Eurasia, and they gnaw through tree trunks in order to fell trees so that they can consume the bark. They also use wood to construct lodges and dams.

The fossil record shows that beavers came in a much wider variety of shapes and sizes than they do today. One species was Castoroides, the giant beaver, common throughout North America during the Ice Age. It was the size of a black bear.

Palaeocastor was different, as it does not appear to have lived in or around the water at all. It was smaller than its modern cousins. While living beavers use their bucktooth-like incisors to gnaw through wood, Palaeocastor used its teeth for digging. We know this because the shape of their teeth matches the scratch marks left on the walls of their burrows.2

The fact that we find so many of their burrows in close proximity to each other suggests that they lived in colonies, like prairie dogs do today. They probably behaved a lot like prairie dogs too, grazing on the low-growing vegetation instead of bark and aquatic plants. Their burrows occur at different levels throughout nearly 150 feet of sedimentary rock.4 This suggests several generations of beaver colonies inhabited the area over time.

Exactly why they constructed corkscrew-shaped burrows is unknown. But scientists suggest it might have kept their nests at a constant and comfortable temperature and humidity.

Were the Burrows Made Before, During, or After the Flood?

There is disagreement among young-earth paleontologists as to how much of the fossil record formed during the worldwide flood of Noah’s day. Some think that almost the entire fossil record (up until the Ice Age deposits) formed during the flood. Others think that the flood formed some minor part of the fossil record. Various “middle ground” positions also exist between these two extremes. In his recent publication in the Answers Research Journal, creation researcher Chad Arment suggests that Palaeocastor burrows may provide a helpful clue.5

Obviously, a living organism created these burrows. And because burrows cannot be picked up and transported, they must have been created where they currently exist. These facts help narrow our options in figuring out when Paleocastor built their burrows.

Before the Flood?

Before the flood, God declared that all land-dependent life not on the ark was to be destroyed with the earth (Genesis 6:13). The surface of the earth itself was destroyed (Genesis 9:11). Such catastrophic processes would have certainly obliterated any Palaeocastor burrows around at the time. Additionally, all current flood models agree that the sedimentary deposits in which the burrows are preserved formed either during or after the flood. This is the case regardless of how much of the fossil record formed during the flood.

For these reasons, Arment argues that this hypothesis for when Palaeocastor burrows formed is the least likely of the three.

During the Flood?

Some creationists argue that Palaeocastor formed their burrows during the flood. They believe that these beavers survived the initial onslaught of the flood and made temporary dwellings on briefly exposed sedimentary deposits laid down earlier in the flood.

Arment does not believe this scenario accounts for the complex sequence of events that led to the preservation of the burrows. Many Palaeocastor burrows have been found filled with roots from grass and other low-growing plants that infiltrated the burrow walls.2 Normally, the burrow residents would have cleared out the excessive plant growth. But once abandoned, roots quickly took over in the beavers’ absence. After which, the plant roots underwent silicification. This is a petrification process where silica-rich fluids seep into the voids of the roots and replace the original material with a mineral called silica. These roots would not have taken long to decay under normal circumstances, so scientists believe the silicification process must have occurred within a few years of the plants’ death. Once silicified, the roots helped to further stabilize the burrow walls, helping to preserve them as well.

Since different generations of Palaeocastor colonies built their burrows in different layers within the same region, this burrow-abandon-silicify process would have to occur multiple times. For these reasons, Arment argues that they are not likely to have formed during the flood.

What About Other Fossil Burrows?

We should acknowledge that Palaeocastor burrows are not the only burrows in the fossil record. In fact, burrows occur throughout the fossil record. Many of these are found in portions of the fossil record that most young-earth paleontologists agree formed during the flood. How can we explain these?

Arment points out that the evidence for the extensive growth of intrusive plant roots is a rare phenomenon in the fossil record. Since most fossilized burrows lack such features, many of them possibly formed during the flood. Perhaps animals created them, trying to escape the floodwaters by burrowing into the mud or sand.

Palaeocastor: Witness to a Changing World

Arment suggests that the best explanation for when the beaver burrows formed is after the flood. Unlike wetland-loving beavers of our day and age, paleontologists believe that Palaeocastor lived in an open grassland environment with a semi-arid climate, much like modern prairie dogs. This is indicated by rounded clods of clayey soil present in these sedimentary deposits where the burrows are found.

This corresponds well with the Arphaxadian epoch on the young-earth timescale. This chunk of time underwent huge changes in the climate as the earth resettled after the flood and entered the post-flood Ice Age. Fossils suggest that conditions shortly after the flood were very wet, balmy, and experienced heavy rainfall. Places like Wyoming were home to a variety of subtropical plants and animals, such as those found in the Green River Formation. But as the climate became cooler and drier, the dense forests disappeared and were replaced by open grasslands before the Ice Age began.

Palaeocastor was a living witness to the time in between these climate extremes. Similar ancient environments have been reconstructed from other fossil sites, including the Agate Fossil Beds and the Ashfall Fossil Beds, both from Nebraska.6,7 In their study of the latter fossil site, researchers suggest that grasslands characterized much of North America at this time, with occasional lakes and trees scattered across the landscape. The environment would have sustained herds of grazing mammals, some of which were even similar to those we have today, like rhinoceros, camels, and horses.

But this amazing world did not last forever. It was but one environment of many on the grand stage of the march of time. Palaeocastor was a witness to the incredible changes happening in its world. And it could watch it all unfold from the relative safety of their corkscrew-shaped homes underneath the soil.

Conclusion

Much creation research has been devoted to the flood and the post-flood Ice Age following. But Arment suggests that the Arphaxadian epoch deserves more attention and that creation researchers should be on the lookout for more clues that could help us better delineate which fossils and rocks are from before, during, or after the flood.

The Arphaxadian epoch was a time when significant changes to the earth and its inhabitants occurred. By learning more about them, we can get a better understanding of their place in the overall history of creation. Arment hopes that his research on Palaeocastor burrows will help bring attention to this incredible period of time and allow for a more introspective view of how our modern world recovered from the catastrophism of the flood.

References

- Barbour, Irwin. [sic] H. (1892). “Notice of New Gigantic Fossils.” Science 19(472) (February 19): 99–100.

- Martin, Larry D., and Debra K. Bennett. 1977. “The Burrows of the Miocene Beaver Palaeocastor, Western Nebraska, U.S.A.” Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 22, no. 3 (October): 173–193.

- Barbour, Erwin Hinkley. (1896). “Nature, Structure, and Phylogeny of Daemonelix.” Bulletin of the Geological Society of America 8, no. 1 (January 1): 305–314.

- Hunt, Robert M. Jr. (1990). “Taphonomy and Sedimentology of Arikaree (Lower Miocene) Fluvial, Eolian, and Lacustrine Paleoenvironments, Nebraska and Wyoming; A Paleobiota Entombed in Fine-Grained Volcaniclastic Rocks.” In: Volcanism and Fossil Biotas, edited by Martin G. Lockley, and Alan Rice, 69–111. Boulder, Colorado: Geological Society of America Special Paper 244.

- Arment, C. (2023). “Palaeocastor Burrows as Post-Flood Biostratigraphic Markers.” Answers Research Journal, 16, 183–187.

- McClenagan, Don. 2022. “Mammalian Megafauna Bone Beds of North America: Agate Fossil Beds National Monument and Cita Canyon, Texas.” Creation Research Society Quarterly 59, no. 1 (Summer): 4–13.

- Akridge, A. Jerry, and Carl R. Froede, Jr. 2005. “Ashfall Fossil Beds State Park, Nebraska: A Post-Flood/Ice Age Paleoenvironment.” Creation Research Society Quarterly 42, no. 3 (December): 183–192.