[Originally published as Engineering the Giant Anteater]

If we decided to engineer an animal to keep a check on the population of termites and other similar insects, could we even imagine an improvement over the giant anteater? Would it be possible to realistically imagine modifications to the designs of other existing or extinct animals in order to meet the desired goals?

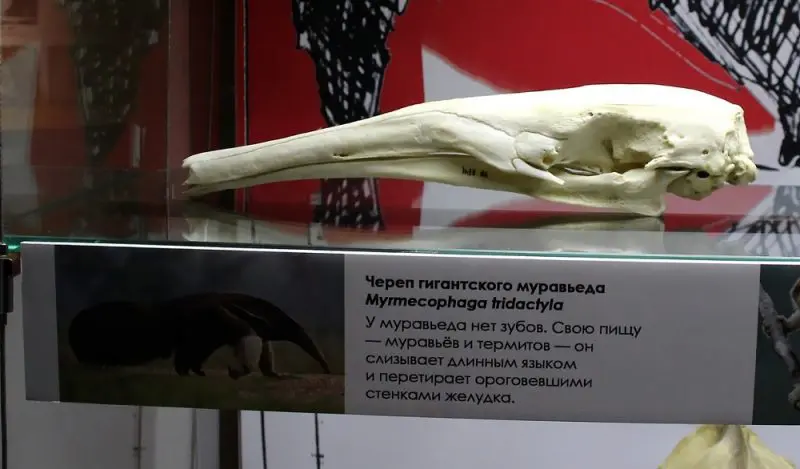

While armadillos and pangolins have an insect diet similar to anteaters, there are clearly large differences between them and the giant anteater, Myrmecophaga tridactyla.

Giant anteaters are part of a unique animal family.* They live in the grassland, swamps, and lowland tropical forests of South and Central America. They grow to be six to eight feet long and 50 to 90 pounds, with males 10 to 20 percent heavier than females.

The Ultimate Insect Collecting Head

The anteater’s most noticeable feature is its unusual long slender snout. Its mouth is quite small and only opens to a small oval. Its foot-long, toothless head is almost tubular in shape holding its 12 to 24 inch-long tongue is longer than its head and is covered in tiny, backward-facing spines. It has salivary glands that secrete a thick, sticky saliva that coats its tongue.

All of this design works flawlessly to convey a load of insects through its mouth into its stomach.

Other Amazing Features

The anteater does not have a stomach that secretes hydrochloric acid as is common in mammals. Instead, its stomach is designed to incorporate the formic acid content of the insects that it eats for the digestive process.

The giant anteater has powerful forearms and sharp claws that it uses to rip open termite and ant nests. Its four-inch-long front claws are kept sharp as its toes flex to the side when walking. These claws make it possible for the giant anteater to climb trees, although it does this only infrequently.

With a sense of smell some forty times better than a human, it can detect its food from a considerable distance.

Putting it All to Work

Once a nest is located the anteater rapidly goes to work. Usually, a small hole is dug into the nest, and the anteater licks up the insects as they emerge. Its tongue moves rapidly in and out at a rate of up to 150 slurps a minute, taking larvae and cocoons as well as insects.

The incoming nourishment is crushed against the hard palate before being swallowed. The complex reciprocating mouth operation is unique in the animal kingdom and is unsurpassed for the rate of insect food intake.

Giant anteaters are choosy about the type of ants and termites that they will consume. They avoid eating the aggressive soldier types of ants and termites that have large jaws.

Sustainable Collecting

I think it interesting that anteaters utilize each ant or termite nest for only a short time, taking less than 200 insects each feeding. They cause little permanent damage to nests and move on from nest to nest to get their daily food requirement of up to 35,000 insects a day. This behavior points toward an instinct designed for the conservation of the food source to the advantage of the insects as well as the anteaters.

Giant anteaters are generally solitary but do manage to mate in the fall, and a single youngster is born in the spring. The young are precocious and are born with sharp claws that allow them to climb onto their mother’s back. The youngling may continue to ride around on its mother’s back for up to a year even though the weaning stage occurs at about six months. Sexual maturity is reached at about two years of age.

All anteaters have low metabolic rates, and giant anteaters have the lowest recorded body temperature for a placental mammal of only 90.9° F. Giant anteaters scoop out shallow depressions in which they rest for up to fifteen hours a day. They stay hidden by covering themselves with their huge fan-like tail.

In Conclusion

It is difficult for me to imagine how any animal could be better engineered to perform the function of checking the population of ants and termites. If evolution is the reason for the existence of this marvelous animal, ask yourself, what did it evolve from and how could this ever happen?

No, I think we must thank God for this creation of the giant anteater!

Footnote:

Only two other members are currently assigned to the Myrmecophagidae family:

1. Tamandua (Tamandua Mexicana and Tamandua tetradactyla).

2. Silky anteater (Cyclopes diactylus).

I did not realize what this amazing animal was like. This is a great article. Sometimes in these busy digital lives we forget to step back and explore these unique animals of God’s creation. We just take for granted that there’s a whole lot of animals we will never see or hear about. I’ve always enjoyed the Creation Magazine as it’s amazed me how unique each animal is after reading things I didn’t know about them. I’m sure I’ve seen an anteater in a zoo, but it would have been a long time ago! Thanks for this study. Praise God for his wonderful creations he gives us to enjoy – animals as pets, work animals, ocean creatures to wonder at, plants and animals for food, beautiful scenery all over the world, the enormous heavens. What an awesome God we have!