In 1821, a 22 year old Charles Darwin boarded the HMS Beagle and departed Plymouth, England to sail on a 5 year voyage around the world. As the ship’s naturalist, Darwin collected thousands of plant and animal specimens. But it was his stint on the Galapagos Islands in 1835 collecting birds that, as this article in PBS’s Evolution Library puts it, “would change the world of science.”

When Darwin returned from his trip he presented his specimens to the Zoological Society of London, where they ended up in the hands of the well-respected ornithologist John Gould. Gould reported that these birds were, “‘a series of ground Finches which are so peculiar’ as to form ‘an entirely new group, containing 12 species.'” It was the study of these finches that inspired Darwin to formulate his theory of evolution by natural selection, which is laid out in his book, “On the Origin of Species” published in 1859.

A glimpse into the field of evolutionary biology today will tell you that scientists have certainly taken this concept and run with it. As Rosemary and Peter Grant write in their 2003 article, “What Darwin’s Finches Can Teach Us about the Evolutionary Origin and Regulation of Biodiversity,” “The present is known; the past is inferred.” In context the Grants are referring to the inference of history of the Galapagos finches. But Darwin’s finches are now an iconic example of a much greater inference. This citation from Live Science’s article, “What is Darwin’s Theory of Evolution” explains:

Natural selection can change a species in small ways, causing a population to change color or size over the course of several generations. This is called ‘microevolution.’ But natural selection is also capable of much more. Given enough time and enough accumulated changes, natural selection can create entirely new species, known as ‘macroevolution.’ It can turn dinosaurs into birds, amphibious mammals into whales and the ancestors of apes into humans.

Do Darwin’s finches support a leap in inference of this magnitude? Let’s examine the Galapagos finches more closely to see the picture that emerges.

The Grants

WIRED magazine hails Rosemary and Peter Grant as “The Legendary Biologists Who Clocked Evolution’s Astonishing Speed.” You could say that in their work, the Grants have functioned as Darwin’s torch-bearers. They meticulously studied the Galapagos finches for almost 40 years. From 1973 to 2012, Singer writes, “the couple tagged roughly 20,000 birds spanning a least eight generations…They tracked almost every mating and its offspring, creating large, multigenerational pedigrees for different finch species. They took blood samples and recorded the finches’ songs, which allowed them to track genetics and other factors long after the birds themselves died.”

In his book, Darwin Devolves, Michael Behe explains why the Galapagos Islands are a perfect location for this research:

Although the Galapagos Islands are located in the open ocean, smack on the equator, the climate is surprisingly variable. On the up to mile-high volcanic structures there are many different niches: beaches; arid lowlands; intermediate climates; and cooler, wetter highlands. The amount of rainfall is one of the most important determinants of the quality of vegetation that will grow and consequently of how many seeds are available for bird food.

It is the response of the finch populations to the available food supply that have overturned a key Darwinian paradigm.

The Process of Evolution- Fast or Slow?

Over their 40 years of research the Grants have documented an ongoing cycle. Depending on various climate related factors, the Galapagos Islands yield an environment that oscillates in its favorability toward finches with particular features. Behe summarizes the finch variations:

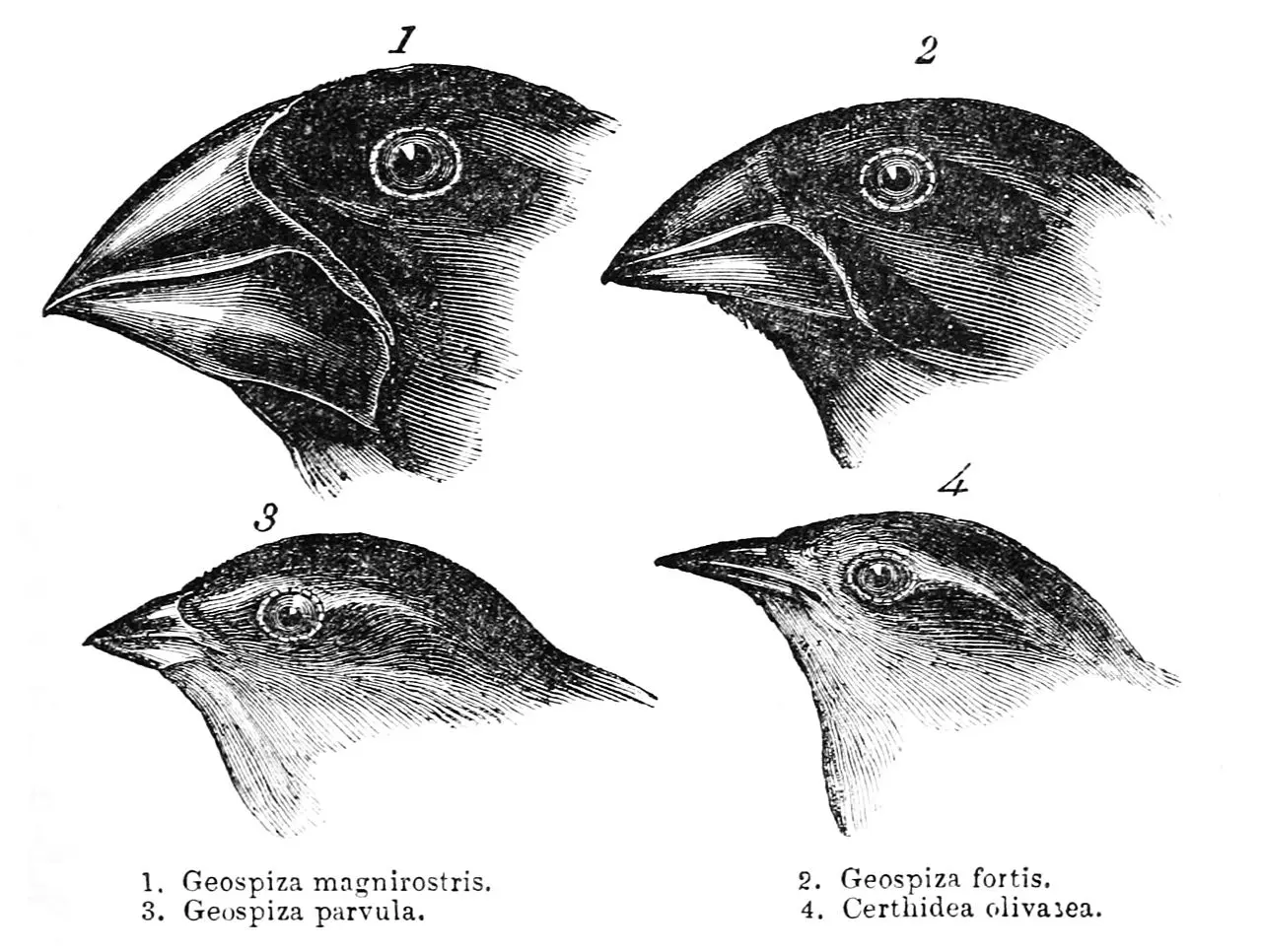

They range in size from about 4-8 inches in length and .25 to 1.25 ounces in weight. The species are divided into four groups (genera) based on where they live, what they eat, and other characteristics…the birds eat whatever they can get in their beaks, including plant products (seeds, plant buds, nectar, fruit) and animals (insects, shellfish, eggs or seabirds)…Some have thin, probing beaks, which help the birds collect nectar; others have thick, stubby beaks, good for breaking open seeds. The bigger the beak and the bigger the bird, the better it can crack tougher seeds.

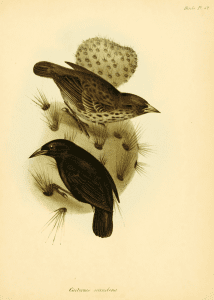

The illustrations below are from John Gould’s book, The Zoology of the Voyage of the H.M.S. Beagle, under the command of Captain Fitzroy, R.N., during the years 1832-1836, Part 3, Birds, and are the work of his wife, Elizabeth Gould.

Thanks to the Grants, we now know that natural selection results in a process of evolution which is apparently much faster than had been previously thought. The Grants witnessed adaptations occur in just one generation.

When Peter Grant was asked, “What are the biggest changes you’ve seen over the last 40 years in our understanding of evolution,” he replied,

From our study and others, I think the general concept of the rate of evolution has changed. It’s a much more rapid process than it was thought to be. When we started, most people would have been skeptical that you could get evolutionary change in one generation- producing a bird with a more pointed beak, for example. The idea that the effects of natural selection are so minute that you can’t measure them has been thrown out.

Behe asks the important question: “What does such incessant, back-and-forth selection eventually yield?” The Grants’ answer can be found in their 2008 work, “How and Why Species Multiply: The Radiation of Darwin’s Finches.” Behe quotes:

“Over the term of many long decades, centuries, or longer there could be a net trend towards a larger or smaller overall beak size.”

Do these results support the optimistic claims about the evolutionary end product of natural selection so often found in biology textbooks? Can we, as the Live Science contributor above says, get whales from amphibious mammals or humans from the ancestors of apes? If we take the Grants’ findings into consideration, the prospects don’t look good.

Historical Inferences

Viewing the Grants’ findings through their own lens of deep time, the finches don’t support such ambitious conclusions. In the following quotes the Grants describe their historical inferences on finches and on the Galapagos Islands:

The closest genetic relatives of Darwin’s finches on the South American continent, in Central America, and in the Caribbean are a group of seed-eaters (Tiaris and relatives) allied to tanagers…Darwin’s finches diverged from them in the last 2 million or possibly 3 million years, according to calculations based on an assumed molecular clock applied to mitochondrial DNA and allozyme data…

Just for reference, the illustration below, also from Gould’s book, is a bird from the tanager family- the finch relative:

Three million years ago, there were far fewer islands than today, perhaps only five…Climate changed as well. The average air temperature declined, but more important that this, the world’s climate underwent a sharp transition 2.75 million years ago with the abrupt onset of glaciation…In the last million years the climate has oscillated between glacial and interglacial conditions at about 100,000-year intervals.

Behe comments on how underwhelming the Grants’ findings are with respect to supporting the ultimate results of evolution that we’ve seen asserted:

Thus the same variation, mindless selection, and relentless evolution of birds that the Grants have recorded so admirably for decades has actually been going on for about one million generations- tens of thousands of times longer– and involving a cumulative total of billions of birds. The results of the ‘net trend’ produced by all that frenetic Darwinian evolution is a twofold variation in body length, shorter or longer beaks of greater or lesser depth…and not much else. Beginning with something very much like a finch, Darwinian processes labored long and mightily in the Galapagos and brought forth…a finch.

So, if a couple million years of fierce evolution has brought us finches from a finch-like ancestor, what can we reasonably expect from these same processes a few million more years down the road? After all, no Creationist would deny the ability of natural selection to yield the extent of changes we’ve seen so far in Darwin’s finches. Is it possible the finches just need more time to experience greater transformation? Or, could it be that there are limits to what evolution can accomplish? We’ll pick up there in part 2.

Great article! A finch-like beak on a finch-like ancestor is still a finch! It never was, or never will be a “Finch-billed Iguana” or a “Finch-billed Raccoon”! Genesis 1:25 “And God made the beast of the earth after his kind, and cattle after their kind, and every thing that creepeth upon the earth after his kind: and God saw that it was good.” Very in depth and I can see a lot of research went into it. (But being a bird lover, I just looked at the pictures! LOL) William

Thank you! I just fell in love with the pictures as well. Makes me want to find Gould’s book just so I can admire his wife’s artwork. 🙂