[Originally published in 2013 as The Bacterial Flagellum: More Sophisticated Than We Thought!]

The bacterial flagellum is a symbol of the Intelligent Design movement, and rightly so. After all, bacteria are commonly recognized as the “simplest” organisms on the planet. Nevertheless, their amazingly well-designed locomotive system has continued to amaze the scientists that study it. In 1996, Dr. Michael Behe highlighted the intricate design of the bacterial flagellum in his book, Darwin’s Black Box. While some have tried to explain it in terms of Neo-Darwinian evolution, they have not come close to succeeding.

Not only is the bacterial flagellum amazingly well-designed, it is far more versatile than anyone imagined.

Some bacteria (like Escherichia coli) have multiple flagella, which makes it very easy for an individual to navigate in water. All the bacterium has to do is adjust which flagella are spinning and how they are spinning, and the single-celled creature can do acrobatics in the water. However, the vast majority of bacteria have only one flagellum. It was thought for a long time that because of this, it is difficult for them to make sharp turns in the water.

Two years ago, this thinking changed abruptly when a group of physicists from the University of Pittsburgh showed that the bacterium Vibrio alginolyticus, which has only one flagellum, can make sharp turns with ease. They showed that in order to execute such a turn, the bacterium backs up, lurches forwards, and swings its flagellum to one side.1 The entire maneuver takes less than a tenth of a second and results in a 90-degree turn. So not only is the bacterial flagellum an exquisite “outboard motor” that propels the bacterium through the water, it is also a rudder that allows the bacterium to make sharp turns at will!

Of course, the question of how the flagellum can act as a rudder is a bit of a puzzle.

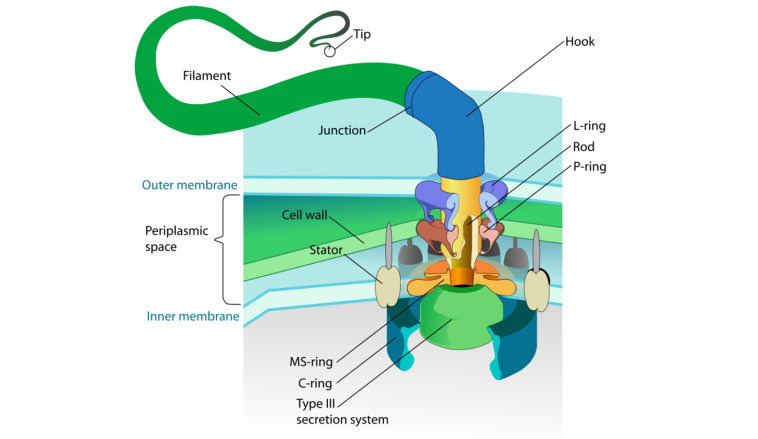

If you look at the diagram above, the flagellum isn’t connected to the bacterium in a way that allows it to pivot, so how does the bacterium manage to swing it to one side, turning it into a rudder?

That question has been answered by a new study published in Nature Physics. The authors of the study show that when the bacterium reverses direction, the hook shown in the illustration above stretches. When the bacterium then begins to move forward, the hook is suddenly compressed. That compression is strong enough to cause the hook to buckle under the stress, and when the hook buckles, the flagellum is thrown to one side. In other words, the bacterium forces the hook to “fail,” turning its motor into a rudder.2

Now here’s the amazing part:

The speed at which the hook buckles is the same as the speed at which the bacterium normally swims. This means that the hook should be buckling all the time, but it only buckles when the bacterium makes a turn. This indicates the hook is stiffer when the bacterium is swimming in one direction. The act of backing up must “soften” the flagellum in some way so that when the bacterium begins forward motion again, the hook buckles under the stress.

As an article about this study in Science News tells us:3

The microbe’s minimalist approach to turning could work for tiny robots, says Bradley Nelson of the Institute of Robotics and Intelligent Systems at ETH Zurich. “It certainly provides inspiration to us to consider designing artificial flagella that also exhibit buckling.”

That’s not surprising, of course. Engineers are usually inspired when they examine the designs of the more talented members of their profession. Where better for an engineer to get inspiration than from the designs of the Greatest Engineer?

References

- Li Xie, Tuba Altindal, Suddhashil Chattopadhyay, and Xiao-Lun Wu, “Bacterial flagellum as a propeller and as a rudder for efficient chemotaxis,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 108(6):2246-2251, 2011

- Kwangmin Son, Jeffrey S. Guasto, and Roman Stocker, “Bacteria can exploit a flagellar buckling instability to change direction,” Nature Physics doi:10.1038/nphys2676, 2013

- Cristy Gelling, “Flagellum failure lets bacteria steer,” Science News, August 24, 2013, p. 17