[Originally published in 2014 as Conflicting Conclusions on Speciation]

Two research studies arrive at conflicting conclusions on speciation, one on Himalayan songbirds and one on Brazilian ants. The songbird research study was published in the prestigious British journal Nature, while the ant research study was published in the American journal Current Biology.

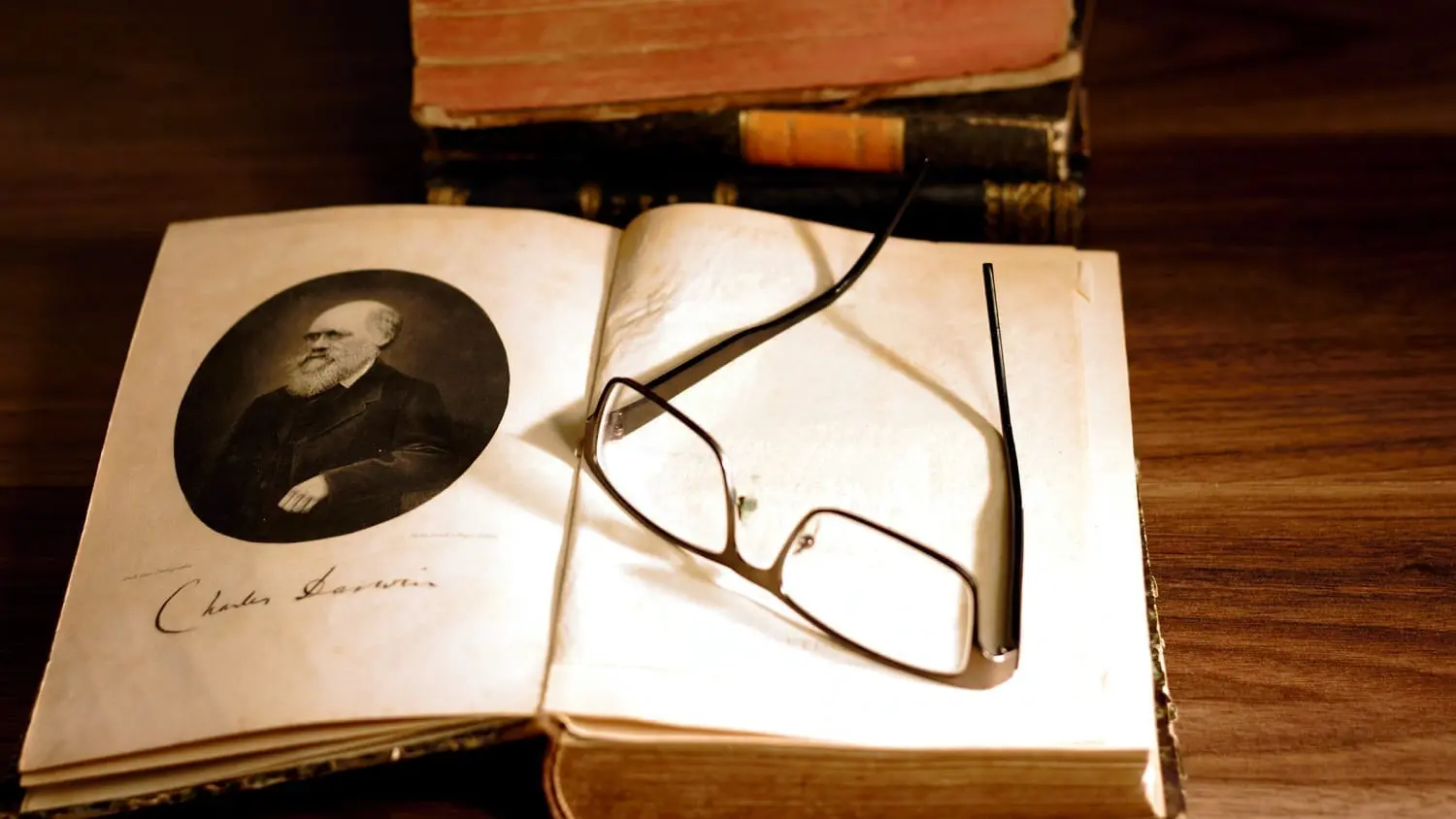

The songbird study was led by Trevor D. Price of the University of Chicago, and the Brazilian ant study was led by Christian Rabeling of the University of Rochester, both highly respected international teams. While the findings in the Himalayan songbird study support Charles Darwin’s speciation theory of geographical isolation, the Brazilian ant’s findings undermine his theory.

Speciation, an evolution term intended to explain how new species might have developed from existing species, is again in trouble.

Songbirds

Speciation in songbirds, according to Price, stems from geographical isolation over long periods.

Speciation generally involves, a three-step process — range expansion, range fragmentation [isolation] and the development of reproductive isolation between spatially separated populations.

Today, roughly 4,000 songbird species comprise almost half of all modern bird species. Songbirds, known as Oscines (from Latin oscen, “a songbird”), are characterized as having a vocal organ to produce diverse and elaborate bird songs. Within Asia, the Himalayas are home to more than 460 songbird species that are found nowhere else, with more than 360 of those species occurring in a narrow band stretching from eastern Nepal through China, India, and Myanmar.

How and why did this unique species-rich songbird community pop up in the eastern Himalayas? By combining decades of field surveys, DNA analyses in association with other research conducted by an international team of experts from India, the USA, Germany, and Sweden, Price’s team concluded that speciation was due to “range expansion” and “range fragmentation,” as expected from Darwin’s theory of geographical isolation.

Allopatric Speciation

Geographical isolation leading to the formation of new species is popularly known as allopatric speciation. Allopatric is from the ancient Greek word allos, meaning “other” + Greek patris, meaning “fatherland.” Two chapters in The Origin of Species, entitled “Geographical Distribution,” were dedicated to explaining this theory. Darwin highlights the importance of geographical distribution:

If the difficulties be not insuperable in admitting that in the long course of time all the individuals of the same species, and likewise of the several species belonging to the same genus, have proceeded from some one source; then all the grand leading facts of geographical distribution are explicable…

Looking to geographical distribution… we can understand, on the theory of descent with modification, most of the great leading facts in Distribution.

The University of California’s Understanding Evolution website section on “Causes of Speciation” includes three causes:

- geographical isolation,

- reduction of gene flow,

- and reproductive isolation.

Geographical isolation with natural selection has long been a cornerstone theory for the evolution industry.

If Darwin’s geographical isolation theory were true, then speciation would be expected to grind to a halt when a species’ range of habitation is restricted to geographical niches. This is what Price thinks happened to the Himalayan songbird. In an interview with the Guardian, a British news agency, Professor Price explained:

Despite the great diversity of environments and ability for species to move between areas, [they don’t, and] evolution [then] in the eastern Himalayas appears to have slowed to a basic halt.

Brazilian Ants

The Rabeling’s research team, however, reports evidence undermining Darwin’s long-held geographical isolation theory. The game-changing findings were reported in an article written by science writer Max Kutner and published on Smithsonian.com. titled: “This Ant Species May Support a Controversial Theory on Evolution” with the subtitle “New research suggests that species don’t have to be geographically separated in order to evolve.” Kutner reported:

German researcher Christian Rabeling was digging up ant colonies on a college campus in Brazil when he found something unexpected—certain ants appeared smaller and shinier and had wings. Rabeling soon realized that those strange ants belonged to a previously undocumented [different] species, a parasite that was feeding off the nutrients of the already familiar ants.

Conflicting Conclusions

At the center of the controversy around these findings is the validity of Darwin’s allopatric speciation theory. Contrary to Price’s findings of allopatric speciation, Rabeling developed an evolutionary concept called sympatric speciation. According to the sympatric speciation theory, new species can arise from the same geographic region — and should not have “slowed to a basic halt,” as claimed by Price’s team.

“But,” according to Kutner, “Rabeling and Schultz believe they’ve done it.”

The ant colony that Rabeling’s team studied was discovered on the campus of São Paulo State University. Under a group of eucalyptus trees, the familiar fungus-farming ant, Mycocepurus goeldii, was found coexisting in the same colony with a parasite ant known as Mycocepurus castrator who was eating the food reserves produced by M. goeldii and reproducing.

Jerry Coyne of the University of Chicago was skeptical of the findings. In an interview with Kutner, Coyne said:

Unless they have evidence that this phenomenon actually occurred in geographic isolation…then the case is not convincing… Just saying that you have sister species of ants and that one is parasitic on the other, is evidence of sympatric speciation, is not correct.

Mycocepurus goeldii and Mycocepurus castrator proved to be two distinct species when the ants’ genes in the cell’s nucleus and mitochondria were compared.

Even though a trace of a relationship exists between nucleotides in the nucleus, Rabeling demonstrated that the sequencing of the nucleotides in the mitochondria between the two species was completely different. Two similar yet different species live in the same niche.

In an unexpected contradiction to Darwin’s theory, Rabeling said, “We now have evidence that speciation can take place within a single colony.”

Since the evidence for a cohesive mechanism for evolution has failed to have any predictive value, as seen between the songbirds and ants, there is little wonder why a cohesive theory of evolution remains a mysterious mirage. There is no known natural law of biological evolution.

Unexpected – No Consensus

In fact, no cohesive consensus on the mechanism of evolution has withstood further scientific testing. This persistent plague on the evolution industry has now persisted for more than 150 years since the publication of The Origin of Species. Darwin’s dilemma intensifies.

In the book, The Logic of Chance (2011), Senior Investigator National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) National Library of Medicine, Eugene Koonin notes:

There is no consistent trend toward increasing complexity in evolution, and the notion of evolutionary progress is unwarranted… In today’s evolutionary biology…, the main theme is the absence of an overarching main theme.

Genesis

Despite all attempts otherwise, the scientific evidence overwhelmingly continues to undermine biological evolution while continuing to support the Genesis account of creation.