[Originally published as Radiometric Dating: Doesn’t it Show that the Earth is 4.5 Billion Years Old? Part 2]

A basic way to express the rate of radioactive decay is called the half-life. This equals the length of time needed for 50% of a quantity of radioactive material to decay. Unstable radioactive isotopes called parent elements become stable elements called daughter elements. Each radioactive element has its own specific half-life (see Table 1).

Example Radiometric Isotopes and Half-Lives Changing into Stable Elements

Radioactive Parent Element→Stable Daughter Element: Half-Life

- Carbon-14 (14C)→Nitrogen-14 (14N): 5,730 Years

- Potassium-40 (40K)→Argon-40 (40Ar): 1.3 Billion Years

- Uranium-238 (238U)→Lead-206 (206Pb): 4.5 Billion Years

- Rubidium-87 (87Rb)→Strontium-87 (87Sr): 48.6 Billion Years

Note: Carbon-14 is not used to date minerals or rocks, but is used for organic remains that contain carbon, such as wood, bone, or shells.

To estimate a radioisotope age of a crystalline rock, geologists measure the ratio between radioactive parent and stable daughter products in the rock. They can even isolate isotopes from specific, crystallized minerals within a rock. They then use a model to convert the measured ratio into an age estimate. The models incorporate key assumptions, like the ratio of parent to daughter isotopes in the originally formed rock. How can anyone know this information? We can’t. We must assume some starting condition. Evolutionists assume that as soon as a crystalline rock cooled from melt, it inherited no daughter product from the melt. This way, they can have their clock start at zero. However, when they find isotope ratios that contradict other measurements or evolution, they often invoke inherited daughter product. This saves the desired age assignments.

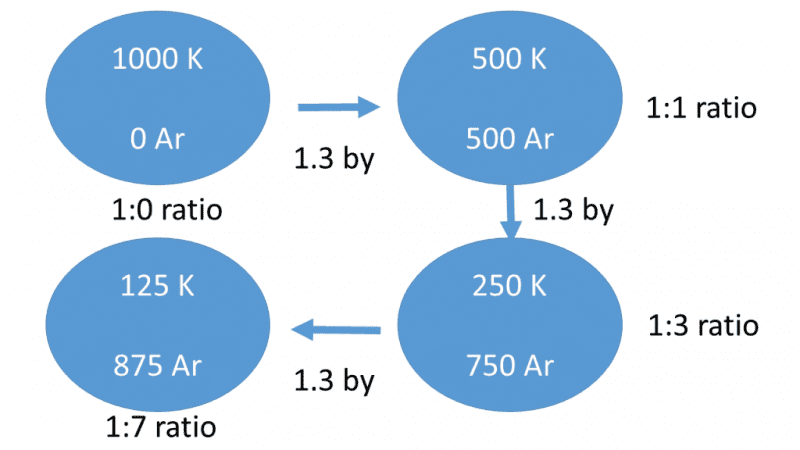

Igneous (crystalline) rocks—those that have formed from molten magma or lava—are the primary rock types analyzed to determine radiometric ages. For example, let’s assume that when an igneous rock solidified, a certain mineral in it contained 1,000 atoms of radioactive potassium (40K) and zero atoms of argon (40Ar).

After one half-life of 1.3 billion years, the rock would contain 500 40K and 500 40Ar atoms, since 50% has decayed. This is a 500:500 or 500-parent:500-daughter ratio, which reduces to a 1:1 ratio. If the sample contained this ratio, then the rock would be declared 1.3 billion years old. If the ratio is greater than 1:1, then not even one half-life has expired, so the rock would be younger. However, if the ratio is less than 1:1, then the rock is considered older than the half-life for that system.

Figure 2. Decay of Radioactive potassium-40 to argon-40. “by” means “billions of years,” K is potassium, Ar is argon. After three half-lives of this system, totaling 3.9 billion years, only 125 of the original 1000 radioactive potassium-40 atoms remain, assuming even decay for all that time.

Figure 2. Decay of Radioactive potassium-40 to argon-40. “by” means “billions of years,” K is potassium, Ar is argon. After three half-lives of this system, totaling 3.9 billion years, only 125 of the original 1000 radioactive potassium-40 atoms remain, assuming even decay for all that time.

Age-dating a rock requires at least these four basic assumptions:

Assumption #1: Laboratory measurements that have no human error or misjudgments.

Measuring the radioactive parent and stable daughter elements to obtain the ratio between them must be accurate, and it usually is. Keep in mind that most laboratory technicians believe in deep time. This sets the time periods they expect. They all memorized the geologic time scale long before they approached their research, and thus may not even consider that processes other than radioisotope decay may have produced the accurately measured isotope ratios.

Assumption #2: The rock began with zero daughter element isotopes.

Next, this technician assumes that all the radioactive parent isotopes began decaying right when the mineral crystallized from a melt. He also assumes none of the stable daughter element was present at this time. How can anyone really know the mineral began with 100% radioactive parent and 0% daughter elements? What if some stable daughter element was already present when the rock formed?

After all, these experts often explain away unexpected radioisotope age results using the excuse that daughter or parent isotopes must have been present when the rock formed. Without knowledge of the starting condition, the use of isotopes as clocks means nothing.

Assumption #3: The rock maintained a “closed system.”

A closed system means that no extra parent or daughter elements have been added or removed throughout the history of the rock. Have you ever seen an atom? Of course not. It is too small, but we must think about this on an atomic level. Decay byproducts like argon and helium are both gases. Neither gas tends to attach to any other atom, meaning they rarely do chemistry. Instead of reacting with atoms in rock crystals, they build up in rock systems and can move in and out of the rocks.

One leading expert in isotope geology states that most minerals do not even form in closed systems. A closed system would retain all the argon that radioactive potassium produces. He emphasizes that for a radioactive-determined date to be true, the mineral must be in a closed system.[iii] Is there any such thing as a closed system when speaking of rocks?

Assumption #4: The decay rate remained constant.

The constant-decay rate assumption assumes the decay rate remained the same throughout the history of the rock. Lab experiments have shown that most changes in temperature, pressure, and the chemical environment have very little effect on decay rates. These experiments have led researchers to have great confidence that this is a reasonable assumption, but it may not hold true.

Is the following quote an overstatement of known science?

Radioactive transmutations must have gone on at the present rates under all the conditions that have existed on Earth in the geologic past.[iv]

Some scientists have found evidence that zircon crystals endured high levels of radioactive decay in the past, as discussed below. This evidence challenges assumption #4.

To illustrate how much radioisotope dating hinges on assumptions, imagine you encounter a burning candle sitting on a table. How long has that candle been burning? We can calculate the answer if we know the candle’s burn rate history and original length. However, if the original length is not known, or if it cannot be verified that the burning rate has been constant, it is impossible to tell for sure how long the candle was burning. A similar problem occurs with radiometric dating of rocks. Since the initial physical state of the rock is unknowable, workers must assume it.”[v]

Brand New Rocks Give Old “Ages”

Scientific literature omitted from public school textbooks reveal radioisotope age assignments much older than the known ages of many rocks. These results first arrived in the 1960s and 1970s, but most of the scientific community still pays no attention. Argon and helium isotopes were measured from recent basalt lava erupted on the deep ocean floor from the Kilauea volcano in Hawaii. Researchers calculated up to 22,000,000 years for brand new rocks![vi] The problem is common. Table 2 gives six examples among many more.

Table 2: Young Volcanic Rocks with Really Old Whole-Rock K-Ar Model Ages.[vii]

Lava Flow, Rock Type, and Location: Year Formed or Known Age vs. 40K-40Ar “Age”

Kilauea Iki, basalt, Hawaii: AD 1959 Ar age: 8,500,000 years

Volcanic bomb, Mt. Stromboli, Italy: AD 1963 Ar age: 2,400,000 years

Mt. Etna, basalt, Sicily: AD 1964 Ar age: 700,000 years

Medicine Lake Highlands, obsidian, California: <500 years Ar age: 12,600,000 years

Hualalai, basalt, Hawaii: AD 1800–1801 Ar age: 22,800,000 years

Mt. St. Helens, dacite lava dome, Washington: AD 1986 Ar age: 350,000 years

The oldest real age of these recent volcanic rocks is less than 500 years. And yet 40K-40Ar dating gives ages from 350,000 to >22,800,000 years.

Potassium-Argon (40K-40Ar) has been the most widespread method of radioactive age-dating for the Phanerozoic rocks, where most fossils occur. The misdated rocks shown above violate the initial condition assumption of no radiogenic argon (40Ar) present when the igneous rock formed. There is too much 40Ar present in recent lava flows. Thus, the method gives excessively old ages for recent rocks.

The amounts of argon in these rocks indicate they carry isotope “ages” much, much older than their known ages. Could the argon they measured have come from a source other than radioactive potassium decay? If so, then geologists have been trusting a faulty method.

If they can’t obtain correct values for rocks of known ages, then why should we trust the values they obtain for rocks of unknown ages?

These wrong radioisotope ages violate the initial condition assumption of zero (0%) parent argon present when the rock formed. Furthermore, the slow radioactive decay of 40K shows that there was insufficient time since cooling for measurable amounts of 40Ar to have accumulated in the rock. Therefore, radiogenic argon (40Ar) was already present in the rocks as they formed.

Radiometric age dating should no longer be sold to the public as providing reliable, absolute ages. Excess argon invalidates the initial condition assumption for potassium dating, and excess helium invalidates the closed-system assumption for uranium dating. The ages shown on the uniformitarian geologic time scale should be removed.