A few years ago, my family was driving through Utah on our way to Seattle, and I got to watch herds of these amazing animals. We were driving on I-70 through Eastern Utah, and the Pronghorns were visible in the stretch between us and the Book Cliffs. They were grazing on the few bushes and grasses left on the high plain in February.

I remember being amazed at how they could survive when the land for hundreds of miles seems to be half-frozen mud with only the occasional sage bush to break up the flatness of the valleys.

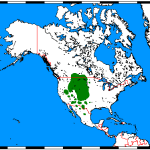

Utah is right in the middle of Pronghorn country. Their range runs from the central plains of Southern Saskatchewan and Alberta (where Winter temps often reach -50), down through the Great Plains of the American West, through Texas, over to California, and on down into northern Mexico. Like the American Bison, the Pronghorn went from abundant populations to near extinction in the early 1900s. There are some groups that are still in trouble, but we are working to increase local populations as much as possible. Numbers are back up near a million total, which is less than 1/30th of what they were in the 1800s.

Unlike the antelope (which they are occasionally compared to), Pronghorns really don’t like to jump, in fact, they would rather crawl under a fence than jump over even a low one. There have been times where they almost starved because they got caught in an enclosed area and they wouldn’t jump out to the plentiful grazing beyond. Because of this, Pronghorns have a much harder time than deer and such with all the fencing in the North American West. This is the main reason their numbers are so low.

The other problem Pronghorns face is that they like to eat a lot of the same plants as cows and sheep. Especially where sheep are feeding, it is difficult for Pronghorns to find enough food to stay healthy. However, Pronghorns can eat a much greater variety of plants then these domestic animals. They are especially fond of flowers and fruit in the Summer months and don’t have problems digesting a lot of plants that sheep and cows have to avoid. They also don’t have to stay near water sources as God designed their systems to be very careful with water.

Turns out these are another one of the Evolutionary-tree stumpers. This time it’s the Pronghorn’s horn/antlers that won’t fit neatly into a group of animals. The horns are made of keratin (the stuff your fingernails are made of) like a sheep’s or cow’s, rather than bone like a deer’s antlers. But late in the Fall of each year, they fall off leaving only a bony center like what you would find under a cow’s for a couple of months.

The other specialty is that the Pronghorn is the only animal with a keratin horn that is branched. That’s how they got the name “prong” horn! I even found a website discussing whether you are allowed to use a Pronghorn’s horn as a Jewish trumpet (Shofar). That would be awesome to hear (although it probably wouldn’t sound too impressive since they’re so small).

Pronghorn’s are mid-sized grazing animals. They grow to a little over 3ft (1m) high and weigh between 75-125lb (34-57kg), with the largest being the dads. They have really good vision with eyes nearly the size of an elephant’s and they always stay in open areas where any predator will be quickly seen and an escape path won’t be slowed down by trees.

This brings us to their coolest feature, their speed. We all know that the Cheetah is the fastest animal still alive today, but they’d be no match for a Pronghorn. A Cheetah can only keep up their speed of 62mph (100 kph) for a couple hundred yards (meters) or they would die of overheating, but not a Pronghorn. They can run up to 55mph (88kph) and can maintain speeds of 30mph (48kph) for at least 20 miles! Only the ostrich can keep up with that kind of speed.

A mother Pronghorn takes as long to grow her babies as a human (250 days). She usually bears twins, but although the little ones can soon run, they are vulnerable to predators and only about 2 out of 5 babies make it to grow up. Pronghorns take just over a year to be adults and can live for up to 12 years, although that isn’t likely in the wild.

In the Summer and Fall, Pronghorns live in small groups with one dad and several moms, but the Winter is different. Turns out my February trip was the best time of year to see the large groups that form then. Hormone levels have dropped then, so the guys aren’t all fighting each other for the ladies!

And God said, Let the earth bring forth the living creature after his kind, cattle, and creeping thing, and beast of the earth after his kind: and it was so. And God made the beast of the earth after his kind, and cattle after their kind, and every thing that creepeth upon the earth after his kind: and God saw that it was good. Genesis 1:24,25

Other websites that I got my info from:

US Fish and Wildlife Service: Pronghorns

National Wildlife Federation: Pronghorn

Desert USA: The Pronghorn “Entirely unique on this planet, the Pronghorn’s scientific name, Antilocapra americana, means ‘American antelope goat.’ But the deer-like Pronghorn is neither antelope nor goat — it is the sole surviving member of an ancient family dating back 20 million years.” Just switch that out for 6,000 years!

Great Plains Nature Center: Pronghorns “The eyes of a Pronghorn are nothing short of exceptional. They can pick up movement as far as three miles away. The eyes are located far back on the head so they can keep watch even while the head is down during feeding. Human eyes need a pair of binoculars to see as well as a Pronghorn.”

And a few details from Wikipedia: Pronghorn