[Originally published in Nov. 2015 as Malarial Evolution Nightmare]

Evolution paradigms increasingly struggle to survive under the weight of new scientific evidence. The malarial evolution nightmare is the latest. “Think of a deck of cards,” said Dan Larremore in an interview with Quanta Magazine science writer Veronique Greenwood.

Now, take a pair of scissors and chop the 52 cards into chunks. Throw them in the air. Card confetti rains down, so the pieces are nowhere near where they started. Now tape them into 52 new cards, each one a mosaic of the original cards. After 48 hours, repeat.

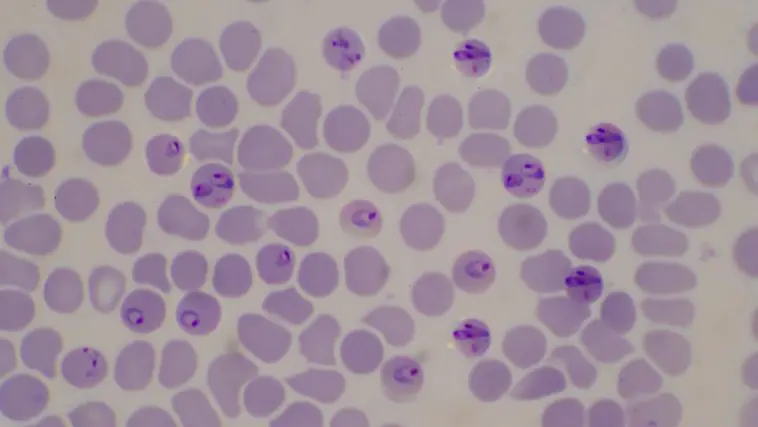

Plasmodium falciparum, the species that causes malaria in humans, uses this complex type of process to evade human immune system detection. As the world’s most dangerous malaria parasite, it is responsible for 600,000 deaths every year and kills more children under the age of five than any other infectious disease on our planet. Greenwood’s card story is a malarial evolution nightmare — the var genes.

Larremore’s cards illustrate the constant gene coup that produces proteins that anchor infected red blood cells onto the walls of the host’s blood vessels clogging circulation. The anchored proteins prevent the parasite from being dragged into the spleen — where it would otherwise be destroyed. P falciparum’s unrelenting virulence stems from this constantly changing nature of the var gene.

Each P falciparum parasite has about 60 of these var (variant) genes, as they are called. As time passes, the parasite uses one gene variant first, then another, presenting a constant flow of differently structured proteins. These constantly changing proteins, technically known as PfEMP1, then cling to the blood vessel, unrecognized by the immune cells that would otherwise spot and destroy it.

But, what is the origin of the var genes?

Chunks and Snippets

The crowning glory of this var gene tactic, though, rises when the parasite divides, which happens every couple of days — the chunks and snippets of the genes during cell division swap places up and down the chromosomes.

In one out of every 500 parasites, this process generates an entirely new gene. With the number of parasites and the number of possible gene variants, the number of probabilities adds up quickly. “It’s crazy. It means the total number of var gene sequences in the world is millions and millions — virtually infinite,” said Antoine Claessens, a malaria researcher with the Medical Research Council, The Gambia Unit, in Fajara.

Paradoxically, according to Larremore, in a recent paper published in Nature Communications, while var genes themselves are never repeated, short sequences of DNA in them — pieces of cut-up card — never change.

“We want to know basic stuff,” said Caroline Buckee, an epidemiologist at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health and a co-author of the new study in an interview with Greenwood. “Are there certain parasites that cause disease more than others? Are they evolutionarily related to each other? … These questions, which in most pathogens we can figure out how to answer, have no answer [in malaria], because we don’t know how to compare these genes to each other.”

Even more importantly, what is the origin of the var genes?

Phylogenic Trees

In looking for these basic answers, the evolution industry has long turned to exploring different phylogenetic tree model options. According to Greenwood, “At the tree’s base is the oldest version of a gene, and as its daughters accrue small differences — a single DNA base change here, a single base change there — they become separate branches. Trees are built by lining the genes up next to each other and checking for differences at each DNA base.”

This phylogenetic tree approach has been used with varying success in developing seasonal vaccines, like the Influenza virus (the flu). Using this approach, however, for developing a malarial vaccine has been like searching for light inside a sequoia redwood tree. Greenwood explains,

All of this means that trees built from var genes are at best difficult to interpret, and at worst misleading, implying relationships where none exist.

In Greenwood’s interview with Martine Zilversmit, a malaria researcher at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City, Zilvermit offered deserved levity:

It’s a mush. That’s the technical term.

To date, all phylogenetic tree models have crashed when re-tracing any possible var gene evolution pathway. “If you want to compare these genes, though, there aren’t many other options,” opined Greenwood.

“It was a case of ‘this is the tool we have,’ and everyone kind of jamming their data into the tool,” said Buckee, who first began to talk about an alternative approach with collaborator Aaron Clauset, now a professor of computer science at the University of Colorado, Boulder.

Buckee, Larremore, and Clauset published a paper (2013) that demonstrated that while such tree networks could pick out identical malarial var gene sequences shared by P. falciparum parasites from different continents — the var genes of the closely related chimp parasite P. reichenowi, even though similar, are distinctly different. The origin of the var gene is the source of the malarial evolution nightmare.

“There have been hardcore malaria vaccine projects going on for 40, 45 years,” Zilversmit ranted to Greenwood. “And it’s been really slow going.”

Paradigm Shift

Since the power of the var gene to continuously produce new complexity remains a mystery, the vaccine industry is taking a paradigm shift.

The Jenner Institute at Oxford University, together with partners Imaxio and GSK, announced November 2, 2015, starting a phase I clinical trial of a novel vaccine candidate (MosquirixTM) aimed at blocking the transmission of malaria — not the proteins produced by the var gene.

Darwin’s dilemma intensifies.

Genesis

Malaria’s var gene underscores the highly complex and unpredictable pattern of nature — a malarial evolution nightmare. Since the origin and evolution of P. falciparum genetics remains a mystery, the origin of the var gene phenomena is more compatible with Moses’ Genesis account than Darwin’s theory of the constant flow of material causes and effects. Nothing is simple in biology.

Evolution exists as a philosophy, not a valid scientific theory.