[Originally published as Rooting the Tree of Life]

I’ve written about phylogenetics numerous times, but I wanted to get into something a little more practical yet deep at the same time: how evolutionists try to root their overarching tree of life.

Most phylogenetic trees focus on small groups of animals. However, for evolution to be true, all life must go back to a common ancestor. That means that evolutionists need to plant the tree of life, aka “root” it, on some likely now-extinct species.

Let’s have a look at how they do it

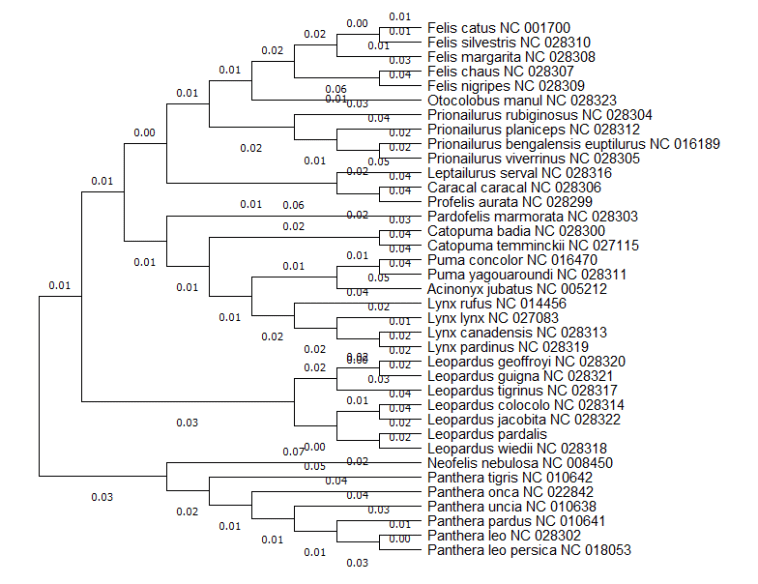

In order to understand what goes on in the evolutionist camp, it is important to know a few terms. The first is outgroup. The outgroup is the term for a group that is used to compare a measured groups with. For example, when I did my article on cat diversification, I built a phylogenetic tree as a proxy for ancestry. I used a non-felid as an outgroup for the tree. The outgroup is also what we root the tree on. In other words, we make the assumption that the outgroup is not closely related to the organisms we are studying and thus it makes a good comparison for the related organism.

The problem becomes, what do you use as an outgroup for the entirety of life? Technically, if researchers wanted to build an accurate tree of all life, an outgroup should be non-living. Obviously, this is impossible. It makes no sense to use something as an outgroup that is non-living. However, this makes it very difficult to root a tree and determine the most recent common ancestor.

To solve this problem, evolutionists appeal to orthologs. Paralogs are genes that were supposedly duplicated in the past, after a speciation event. These paralogs are assembled into what are termed “gene trees.” This is how evolutionists attempt to root the evolutionary tree of life. There is, of course, a giant hole in such logic.

The evolutionists use paralogs to root other paralogs, which then root the evolutionary tree of life: it’s an infinite regress. In an ultimate sense, paralogs root paralogs. How are the original paralogs rooted? They either aren’t rooted at all, or a root is selected arbitrarily according to current evolutionary thinking. Both options are problematic, making it nearly impossible to actually root an evolutionary tree of life.

Why does this matter?

If a tree is not rooted, it is impossible to determine the supposed ancestor of all life, at least phylogenetically. Obviously, such a decision can be made arbitrarily, but that would hardly be a scientific decision. So this is where the circularity comes in. In their view, the common ancestor must exist, so they gladly use paralogs to root other paralogs, which are then used to establish a root for the phylogenetic tree. But this does not work on an empirical level.

Of course, phylogenetics has a lot of other problems since it first assumes evolution is true and then attempts to demonstrate it’s true. Currently, many evolutionists are attempting to argue that there was no universal common ancestor. This argument is a direct response to phylogeny failing to provide an answer for a universal common ancestor. It also creates a lot more problems. Now evolutionists need to have a bunch of diversity prior to the emergence of the common ancestor of the given group. Interestingly (and definitely unintentionally), this is making the model more biblical, something Rob Carter is fond of pointing out.

In a biblical model, ancestry is divided into branching bushes representing an “orchard” of created kinds, an idea that premiered with Kurt Wise. While the evolutionists still hold to a universal ancestor, they are starting to argue that there are multiple branches of the tree of life and multiple groups that led to them. I doubt they will ever completely abandon universal common ancestry, but the mere fact that they are starting to acknowledge that life more closely resembles a bush than a tree is a step in the right direction.

Phylogenetics has lots of problems, and accurately rooting a tree is just one of them. Of course, from a biblical creationist position, rooting a phylogenetic tree is no problem because we don’t assume a universal tree. Instead, we can root trees of each kind on their outgroup, making statistical analysis much simpler for those who choose to use phylogenetics.