[Originally published in 2014 as For Some Diseases, It Was Vaccination, Not Sanitation]

Dr. Wilbert van Panhuis and his colleagues have started an exciting initiative called Project TychoTM. In it, they are taking public health data collected over the years and putting them into an easy-to-access digital system that is open to everyone. They describe the goal of their project in this way:

We aim to advance the use of public health data for the improvement of public health. Oftentimes, restricted access to public health data limits opportunities for scientific discovery and technological innovation in disease control programs. A free flow of data and information maximizes opportunities for more efficient and effective public health programs leading to higher impact and better health. Our activities are focused on accelerating the availability and use of public health data…

They named the project after Tycho Brahe, one of the more colorful 16th-century astronomers. Not only did he live an interesting life, he had a very interesting view of the universe. He made an enormous number of astronomical observations that he meticulously documented, and those observations convinced him that the planets must orbit the sun, not the earth. However, he couldn’t give up the idea of the earth being at the center of everything, so he produced what is probably the most interesting view of the universe ever. As shown in the model above, he put the earth at the center of the universe, and he had the sun and moon orbiting the earth. The rest of the planets were then assumed to orbit the sun, as it moved in its orbit around the earth. While this view of the universe is clearly unworkable, it was incredibly original!

Why would a project involving public health data be named after this colorful character? Because his main contribution to science was the data he collected. While he couldn’t make heads or tails of his data, another astronomer, Johannes Kepler (who was once employed by Brahe) did. Kepler was able to use Brahe’s data to develop three laws of planetary motion that demonstrated all the planets, including the earth, orbit the sun. Sir Isaac Newton was then able to use Kepler’s Laws to develop his Law of Universal Gravitation, which describes how gravity works both here on earth and throughout the universe. Brahe’s data, then, were the foundation of some of the greatest advancements in the field of astronomy in the 16th and 17th centuries.

In Dr. van Panhuis’s view, the data he is collecting could end up being like Brahe’s data. It might be used by other scientists to better understand diseases and how to deal with them as they spread through populations. While I can’t say whether or not that will ever happen, I can say that these data make it easy for me to address a popular myth about vaccination.

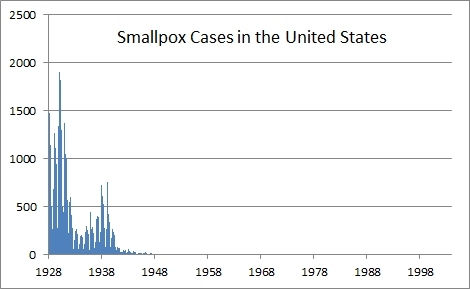

Anti-vaccination groups often suggest that vaccines had little to do with the reduction of diseases like smallpox, polio, and measles. Instead, they insist that better sanitation was the reason these diseases mostly disappeared from the U.S. population. However, a quick use of Project Tycho’s data shows how this is simply not true. I used the system to access data on smallpox, polio, and measles in the U.S. and then graphed the results:

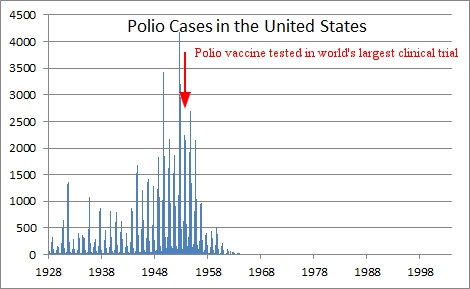

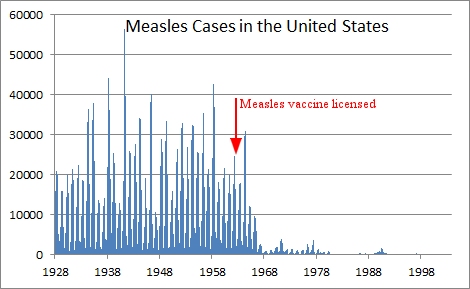

The big thing to notice about these three graphs is that they all include the same years, 1928–2003. By looking at all three of them, you can see that each disease decreased at a different time. Smallpox cases were pretty much nonexistent by 1948. However, that’s when polio cases started to rise! They didn’t start decreasing until 1954, and they didn’t become virtually nonexistent until the early 1960s. Measles cases, on the other hand, stayed fairly steady until the late 1960s and didn’t become pretty much nonexistent until the 1990s. Unfortunately, because people are choosing not to vaccinate, measles is making a comeback in the United States.

The main point here is that if sanitation were responsible for getting rid of these diseases, you would expect them to all decline at roughly the same time. However, they clearly did not. This tells us that while good sanitation is responsible for the reduction of many diseases (such as cholera, dysentery, and typhoid), it is clearly not the reason for the reduction of diseases like smallpox, polio, and measles.

So what caused their reduction? Vaccination. Look at the polio graph. History’s largest clinical trial, which involved over a million children, was conducted on the polio vaccine in the U.S. in 1954.1 Notice how quickly the number of polio cases declined after that.

This doesn’t conclusively demonstrate that the vaccine stopped the disease because correlation doesn’t always mean causation. In other words, the vaccine might not have caused the reduction. Some other event might have happened at roughly the same time as the vaccine trial, and that might be the real cause. However, the results of the vaccine trial showed that the children given the vaccine were significantly less likely to get polio than those who were given an inert injection (called a placebo). This fact, combined with the graph, demonstrates fairly conclusively that the vaccine is what reduced polio in the United States.

The same can be said for measles. The first measles vaccine was licensed for use in 1963.2 Note how quickly the number of measles cases dropped after that year. Once again, this doesn’t conclusively demonstrate that the vaccine caused the decline, but other studies add strong evidence to support that conclusion. For example, when measles outbreaks occur in a school, vaccinated children are more than 20 times (more than 2,000%) less likely to get the disease than the unvaccinated children.3

In the end, then, data such as those collected at Project Tycho demonstrate that vaccines are very effective at preventing certain diseases. This, of course, does not indicate whether or not vaccines are safe. However, I do think there is plenty of evidence to support that fact as well.

References

- Francis Jr T, et al. “An evaluation of the 1954 poliomyelitis vaccine trials: summary report,” American Journal of Public Health 45(suppl):1-50, 1955

- Jeffrey P. Baker, “The First Measles Vaccine,” Pediatrics 128(3):435-437, 2011

- Feikin DR, et al. “Individual and Community Risks of Measles and Pertussis Associated with Person Exemptions to Immunization.” Journal of the American Medical Association 284:3145-3150, 2000