[Originally published as Are We Becoming Less Intelligent?]

Somewhere around 200 BC, a man named Eratosthenes learned that at noon on the Summer Solstice in Syene, a man looking down a deep well would see no light in the well, because his shadow would block all the sunlight. He reasoned that this meant the sun was directly overhead in the city of Syene at that moment.

Well, he lived in Alexandria, which was about 500 miles south of Syene. He measured the length of a pole’s shadow in Alexandria at noon on the Summer Solstice and from that determined the angle at which the sun shined on Alexandria when the sun was directly overhead in the city of Syene.

Why would Eratosthenes do this?

Well, like all ancient natural philosophers (including the Christian ones who would come a few hundred years later), he understood that the earth is a sphere. If you are under the mistaken impression that most ancient people thought the earth was flat, you need to realize that this is a textbook myth that is repeated over and over again but is nevertheless quite false.

Since he knew that the earth is a sphere, he used his measurement to reason that the distance between Syene and Alexandria is about one-fiftieth of the distance around that sphere. He then took the known distance between Syene and Alexandria and multiplied by 50 to get the total distance around the earth. The unit he used to measure distance (the stadium) had different definitions at the time, but assuming he used the one that was typically used for long journeys, his measurement was correct to within 2% of today’s accepted value.1

Does that surprise you?

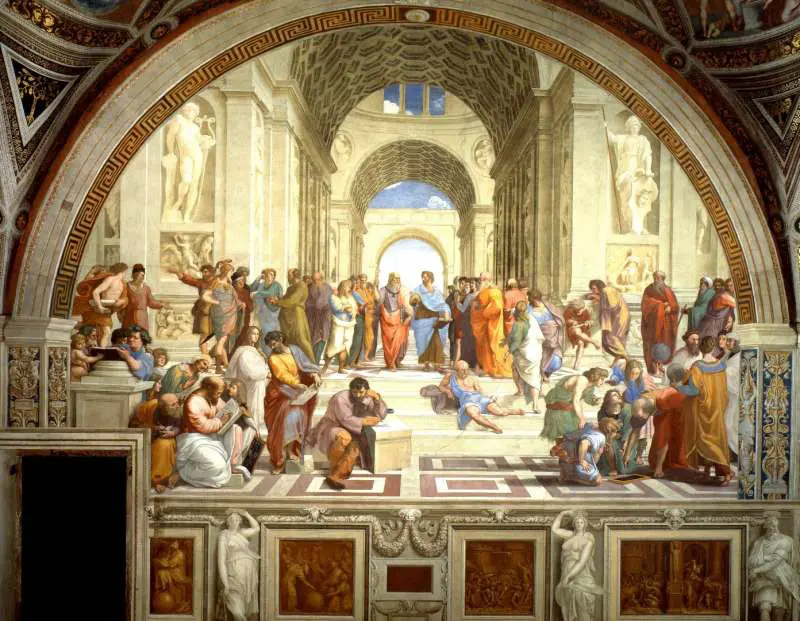

It shouldn’t. In today’s culture, we think of ancient people as ignorant savages, but in fact, many of them were incredibly intelligent. According to at least one geneticist, they were probably more intelligent than we are! In a two-part series published in the journal Trends in Genetics, Dr. Gerald R. Crabtree states:2

I would wager that if an average citizen from Athens of 1000 BC were to appear suddenly among us, he or she would be among the brightest and most intellectually alive of our colleagues and companions, with a good memory, a broad range of ideas, and a clear-sighted view of important issues.

How can Dr. Crabtree make such a seemingly absurd statement?

He argues that our intellectual abilities are governed by all sorts of genes. In fact, based on some studies that have been done on X chromosome mutations that lead to intellectual deficiencies, he produces a conservative estimate that human intelligence is influenced by 2,000-5,000 genes. Based on estimates of mutation rates in the human population, he suggests that this collection of genes must have been affected by many mutations over the past three thousand years. Indeed, he suggests:

…it is very likely that within 3000 years (120 generations) we have all sustained two or more mutations harmful to our intellectual or emotional stability.

In his estimation, then, harmful mutations have collected over the years, reducing our intellectual ability. But why hasn’t natural selection weeded them out? He answers that in the second part of his two-part series.3

He suggests that once we started living in high-density societies, catching diseases from other people was much more likely to cause someone to die than were intellectual deficiencies. As a result, natural selection worked mostly on the genes that govern our immune systems, not on the genes that governed our intellectual abilities.

In addition, societies tend to make people who are intellectually deficient more survivable, because a society can “find a place” for those who would probably die on their own. This sheltered people from the effects of natural selection when it came to intellectual deficiencies. As a result, natural selection could not get rid of the mutations related to intelligence; thus, people simply aren’t as intelligent now as they were 3,000 years ago.

While the good doctor’s proposal is an interesting one, I am not sure he makes his case.

Indeed, in the same journal, another geneticist (Dr. Kevin J. Mitchell) argues against his position, pointing out studies that seem to indicate that intelligence-related genes are not sustaining a high mutation load. He also argues that the complex social interactions used in societies actually produce increased intelligence in future generations.4 As he concludes:

Thus, despite ready counter-examples from nightly newscasts, there is no scientific reason to think that we humans are on an inevitable genetic trajectory towards idiocy.

I honestly don’t know who has the better argument here. I do think that Adam and Eve had mutation-free genomes, which would tend to imply that everything about them was better than we are today. At the same time, however, the Creator has designed our genomes to be adaptive, allowing the human population to change over time to meet our changing needs. As a result, even if we are carrying around some mutations in our intelligence-related genes, it’s not clear that we are significantly less intelligent than our ancient ancestors.

I do hope that more research is done on this question, because I find it incredibly interesting. If nothing else, I hope it helps to dispel the absurd notion that ancient people were intellectually inferior to us!

References

- Kelly Trumble, The Library of Alexandria, Clarion books 2003, p. 24

- Gerald R. Crabtree, “Our fragile intellect. Part I,” Trends in Genetics, 2013, http://dx.doi:10.1016/j.tig.2012.10.002

- Gerald R. Crabtree, “Our fragile intellect. Part II,” Trends in Genetics, 2013, http://dx.doi:10.1016/j.tig.2012.10.003

- Kevin J. Mitchell, “Genetic entropy and the human intellect,” Trends in Genetics, 2013, http://dx.doi:10.1016/j.tig.2012.11.010