[Originally published in 2013 as The Plastisphere]

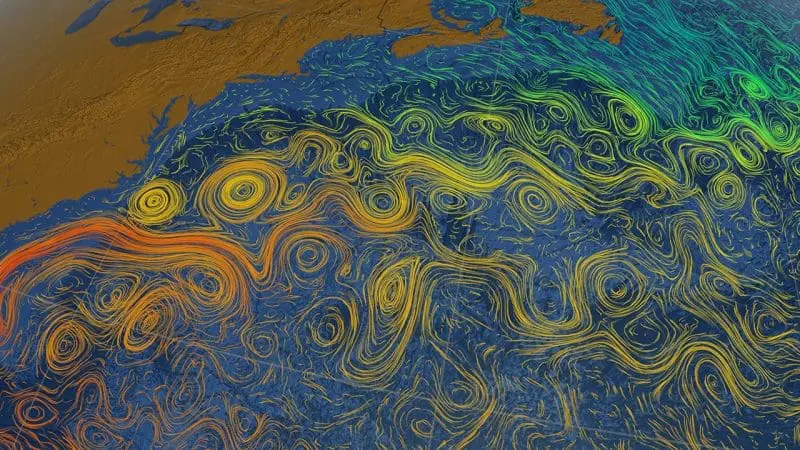

Quite a while ago, I wrote an article about the Great Pacific Garbage Patch, which ended up being included in a book entitled Opposing Viewpoints Series – Garbage & Recycling. While the magnitude of the problem is severely overstated in nearly every popular treatment of the subject, it is a real problem. It came about as a result of the fact that some of the plastic which is not disposed of properly ends up in the oceans. A lot of that plastic gets stuck in gyres – permanent circular currents that exist in distinct regions of the seas. In most cases, once the plastic gets stuck in the gyre, it doesn’t leave.

So what happens to this plastic over time?

Does it decay? Does it just float there forever? How badly is it affecting the ecosystem of the gyre?

A new paper published in Environmental Science and Technology attempts to partially answer these questions. The authors sampled plastic marine debris (PMD), as well as the water in which it was floating, from several different spots in the North Atlantic. They then studied it with a scanning electron microscope (SEM), Raman spectroscopy, and DNA sequencing.

The results were fascinating!

The authors found a rich diversity of microscopic organisms living on the plastic. In fact, the diversity was so rich that they have decided that the plastic supports its own little biological community. As a result, they call the plastic and the organisms living on it the Plastisphere. It’s probably correct to think of it this way because the organisms living on the plastic are quite different from the ones living in the water where the plastic floats.

Consider, for example, just the bacteria they found. Using all of the techniques listed above, they separated the bacteria into 2,815 different types, which they called Operational Taxonomic Units (OTUs). What this means is they didn’t identify exact species. They just grouped the bacteria according to similarity. Most likely, there are lots of species within each OTU.

It turns out that 1,603 of these OTUs were found only in the water, while 1,026 of them were found only on the plastic. The plastic and water shared a mere 186 OTUs! In other words, most of the bacteria living on the plastic were quite different from the bacteria living in the water where the plastic was floating!

Another interesting feature of this Plastisphere is that some of the microorganisms seem to be eating away at the plastic. The authors state:

The pits visualized in PMD surfaces conform to the shape of cells growing in the pits, and sequences of known hydrocarbon degraders support the possibility that some members of the Plastisphere community are hydrolyzing PMD and could accelerate physical degradation.

In other words, when they looked at the microorganisms with the SEM, they found some of them sitting in pits that were shaped specifically to fit them. This indicates that the microorganisms “burrowed out” those pits themselves. Also, the DNA analysis indicated that some of the microorganisms were probably those known to decompose the chemicals that make up the plastic. It may be, then, that the ocean has a “clean-up crew” for plastic. This would make sense since we know the oceans have a “clean-up crew” for oil.

Another piece of evidence for the existence of this “clean-up crew” is the size of the plastic in the oceans. As the authors state:

The majority of plastic pieces recovered in all net tows were fragments of less than 5 mm as has been reported in other studies.

The majority of the plastic probably wasn’t in tiny pieces when it went into the ocean, so something must be tearing it down. The authors mention two other mechanisms of plastic degeneration that probably occur in the ocean, but the fact that the majority of the plastic in the ocean is in tiny bits seems to indicate a lot of degradation.

I did find one piece of really good news in the study. The authors state:

Increases in PMD have been documented in the North Pacific Gyre, but despite increases in plastic production, use, and presumably input into the ocean, other studies show no significant trend in plastic accumulation in the North Atlantic Subtropical Gyre or in the waters from the British Isles to Iceland since the 1980s.

They provide references to support these statements.1 The fact that plastic is not accumulating in most of the regions studied indicates that it is being disposed of better or that there is an efficient plastic-degradation process active in the oceans. Most likely, it is a combination of the two.

Despite this fact, it’s not all good news.

Some of the types of bacteria found on the plastic are part of a genus that contains several disease-causing species. This particular study couldn’t identify which species of this genus were there, so the authors can’t say for sure. Nevertheless, they say their study indicates that plastic could be a means by which diseases among marine animals are spread.

I hope a lot more research is done on the Plastisphere because it is, unfortunately, a very real part of the modern oceans.

References

- Here are the references they cite:

Increase in the North Pacific Gyre: Goldstein, M. C.; Rosenberg, M.; Cheng, L., “Increased oceanic microplastic debris enhances oviposition in an endemic pelagic insect,” Biol. Lett., DOI:10.1098/rsbl.2012.0298, 2012

No significant trend in the North Atlantic Subtropical Gyre: Law, K. L.; Morét-Ferguson, S.; Maximenko, N. A.; Proskurowski, G.; Peacock, E. E.; Hafner, J.; Reddy, C. M., “Plastic accumulation in the North Atlantic Subtropical Gyre,” Science, DOI: 10.1126/science.1192321 2010

No significant trend in the waters from the British Isles to Iceland: Thompson, R. C.; Olsen, Y.; Mitchell, R. P.; Davis, A.; Rowland, S. J.; John, A. W. G.; McGonigle, D.; Russell, A. E., “Lost at sea: Where is all the plastic?” Science,

DOI: 10.1126/science.1094559