[Originally published as Engineering the Human Skeleton]

Most people have at least a basic understanding of the human skeleton. There are skeletal reconstructions in doctor’s offices, in science textbooks, and in horror movies. I think most people also take the skeleton for granted until injury or old age makes it clear to them how important their own skeleton is to their individual comfort.

The skeleton is what many have described as an engineering marvel. Consider some of its engineered characteristics and functions:

- It provides rigid support for the body’s organs and protects the brain, heart, lungs, and spinal cord.

- The bones act as mechanical levers, and in conjunction with the muscles and ligaments, allowing the body to move about.

- The bones also contain a large percentage of the calcium, phosphorus, and other trace elements needed for the body to stay alive.

- The skeletal system is the chemical factory where red blood cells, certain white blood cells, and platelets are manufactured. (This work takes place in the bone marrow.)

Engineers today can only dream of being able to someday design and manufacture artificial “bones” for their machines and devices that could repair themselves when broken the way human and other vertebrate bones do. Man has come a long way with the development of strong yet lightweight structural materials over the past few hundred years. But, none of the inventions of men are near the complexity of the bones designed by the Creator Engineer.

Yes, bones are strong, and bone tissue is a complex framework of living elements and minerals in a state of constant renovation. It is extreme foolishness for anyone to teach that our bones and skeletal structure are the results of evolutionary processes over deep time.

There are many details of the skeleton that are amazing and let’s look at just one amazing component of the body in this article. Dr. Stuart Burgess devotes 23 pages of his book, Hallmarks of Design, to the “irreducible knee joint.”

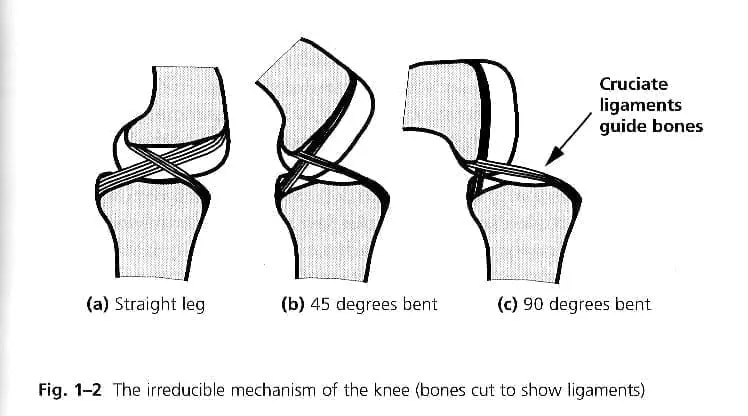

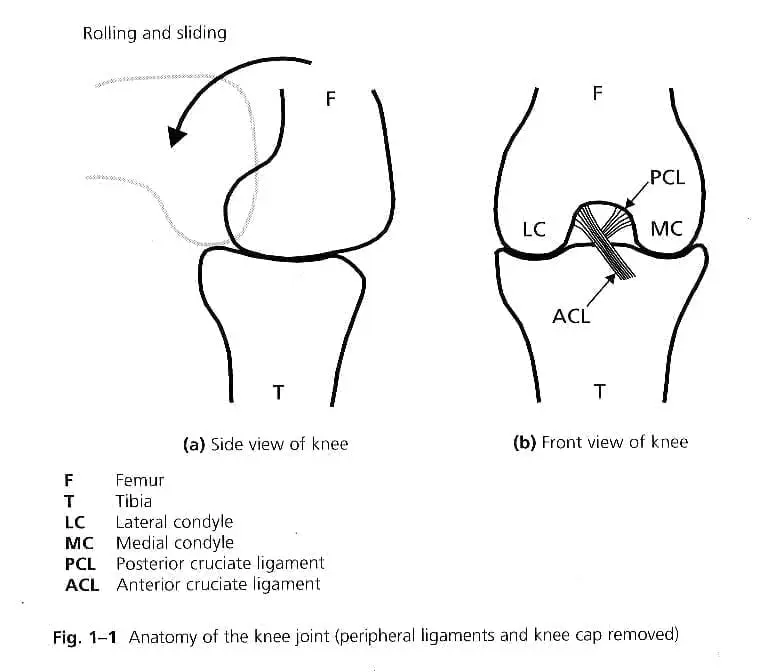

Many people (athletes especially) have experienced serious injuries to their knees that cause them to question the design of the knee. It is often described as a hinge joint—which is true, but it is a very complicated hinge joint that is irreducibly complex. The images below are all from Hallmarks of Design by Dr. Burgess.

The first figure shows the bones and locations of the ligaments connecting them. The figure below shows the sideways view of the ligaments in action.

Dr. Burgess writes,

One important feature of the four-bar mechanism is that it does not have a fixed point of rotation as does a pivot hinge. The knee joint is a particularly sophisticated kind of four-bar mechanism because the cruciate ligaments are kept taut by the rolling action of the bones. In order for the cruciate ligaments to be kept under the right tension, the four-bar mechanism must produce a motion which is exactly compatible with the curved profile of the bones.

Here, again, we see the necessity for all parts of the mechanism to be present with a specific and exact design from the beginning of its operation. It is irreducibly complex. The evolution over time of the knee joint can only be imagined by one with an unbelievable amount of faith in a process never witnessed in reality.