In Part 2 of “Evolution vs Biblical Archaeology,” we considered the Brooklyn Papyrus and its explicit naming of Israelite servants living in ancient Egypt during Egypt’s Thirteenth Dynasty.

We now turn our attention to another ancient artifact, the Soleb Temple “Yahweh” inscription, which provides yet another data point, corroborating the early existence of the Israelites, in contradiction of the widespread claim of secular scholars who allege that the Israelites arose several centuries later.

What is the Soleb Temple Inscription?

The ancient Egyptian Temple in Soleb, in current day northern Sudan, was built by Pharaoh Amenhotep III around the late 15th century BC to the beginning of the 14th century BC, that is to say, right around 1400 BC. It is located at what used to be the southernmost reach of the mighty Egyptian empire, on the edge of Nubia, Egypt’s perennial enemy to the South.

The ancient Egyptian Temple in Soleb, in current day northern Sudan, was built by Pharaoh Amenhotep III around the late 15th century BC to the beginning of the 14th century BC, that is to say, right around 1400 BC. It is located at what used to be the southernmost reach of the mighty Egyptian empire, on the edge of Nubia, Egypt’s perennial enemy to the South.

Inscribed on the pillars of the temple and interior walls are lists of defeated or subdued enemies. These lists also display pictorial images of defeated foes. These claims of conquest could be real or exaggerated, probably a combination of both, and some of the real conquests could possibly be from times before Amenhotep III.

The defeated or subdued enemies are depicted with arms bound behind their backs, captives of war. These bound enemies are depicted according to their people groups, Africans on pillars and walls facing south, Semites on pillars and walls facing north, and so forth. This temple served as a warning from Egypt to Egypt’s rivals and enemies: “Don’t mess with us — or wind up like these other peoples.” The temple and its messages were meant to intimidate foreign nations and establish Egypt’s territory. In other words, it was royal propaganda.

Of particular interest to us here, one of the depictions of defeated or subdued foes mentions “land of the shasu of Yahweh,” and depicts a Semite. “Shasu” is the Egyptian generic word for nomads who travel about, as distinct from people who are settled in towns or cities. Thus, we have the “land of the nomads of Yahweh.”

There has been an attempt by secular scholars to establish the idea that the name “YHWH” inscribed on the temple is a toponym (place name) of a land or city, even though no such city or town or area called “Yahweh” has ever been discovered. This claim is contradicted by the grammatical text of the inscription itself, which contains no land or city determinative, meaning that “YHWH” must be the personal name of the God of these nomads.

Archaeologist Titus Kennedy comments:

“Spelled phonetically, using hieroglyphs to represents the sounds Y-H-W-H-W-A/E, not only do the letters match an Egyptian transliteration, but there is no ‘land’ or ‘city’ determinative, indicating that it must be a personal name rather than a place.

“Since the only ancient people known to have worshipped Yahweh were the Israelites or Hebrews, it follows that these nomads were the Israelites before they settled in Canaan. This inscription is the earliest yet discovered reference to Yahweh, the personal name of God in the Hebrew Bible” (from “Unearthing the Bible,” pg. 61).

The only observation I would add to Kennedy’s comments is that the precise chronology of ancient Egypt is highly disputed among scholars. Some scholars would place the time of Amenhotep III a little later in history. Those scholars then use this preferred chronology to suggest that this could not be the Israelites because the Israelites would not have been still wandering in the wilderness as nomads (“shasu”) at a later date.

This is a moot point because the Israelites remained nomadic after they entered Canaan. Whether the “Yahweh” inscription at Soleb is from the time of the wilderness wandering after the exodus related in the Bible, from the time of Joshua’s military campaigns, or a time after Joshua’s military campaigns, the Israelites were primarily cattle and goat herders and shepherds whose lifestyle was nomadic for a long time after entering Canaan.

Kennedy seems to anticipate this objection of the secular scholars. In the next paragraph, he states: “In the 15th and 14th centuries BC, the people of Yahweh, the Israelites, wandered in the wilderness like nomads, and continued to live a nomadic lifestyle for many years while conquering and settling Canaan.”

Regardless of the precise chronology, this Soleb Temple inscription provides strong evidence of the existence of the Hebrews as a distinct people group whose God was Yahweh at right around 1400 BC.

Details of the Inscription

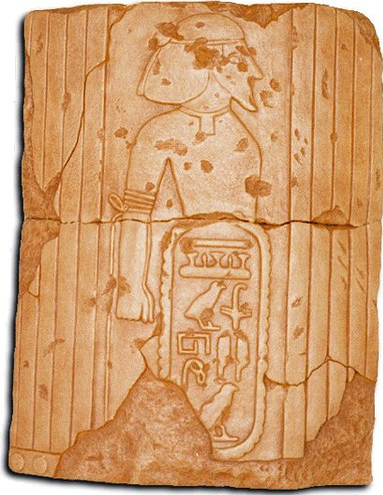

Note the featured image of the inscription at the head of this article. The bound prisoner is depicted as Semitic. Moreover, the inscription faces north, indicating the general direction and location of the people group.

The text is read from right to left, top to bottom. The top horizontal bar figure is the hieroglyphic for “land.” The next three characters form the Egyptian word, “shasu,” in English, “nomads.”

Next, we come to a four-character word.

- The first character shows two feathers which has the phonetic value of the “Y” sound.

- The second rectangular character represents a house and equals the “H” sound.

- The third character shows a knotted rope and has the phonetic value of the “W” sound.

- The fourth is a falcon character that has the “EH” sound.

Thus we have YHWH! That is, Yahweh, as we spell it in English with vowels. There is no doubt whatsoever that these four characters are the Tetragrammaton, the name of the Hebrew God of the Bible. This is a momentous artifact from around 1400 BC, and rich in its implications.

A Secular Scholar’s Perspective on Yahweh at Soleb

Donald B. Redford is a secular scholar who is explicitly contemptuous of the biblical faith in his writings, a reality that needs to be kept in mind when reading the following quote. Redford states:

For half a century it has been generally admitted that we have here the tetragrammaton, the name of the Israelite God, ‘Yahweh’; and if this be the case, as it undoubtedly is, the passage constitutes a most precious indication of the whereabouts during the late fifteenth century B.C. of an enclave revering this god.

In order to avoid the significance of the fact of the existence of the Israelites at that early time in history, some secular scholars claim that “Yahweh” in the inscription is a place name of a town, city, or area, but Redford seems to grasp the futility of this claim. It is particularly noteworthy that, unlike some secular scholars, Redford acknowledges that we have here the word “Yahweh.” There is really no legitimate dispute about this point since the inscription is phonetic in nature. Redford also acknowledges the time frame as being around 1400 BC. More specifically, Redford acknowledges that the word “Yahweh” is the name of the deity.

But, in the face of all these particulars in agreement with the Bible, Redford still wants to deny the truth of Scripture. He suggests that the Hebrews were a tribe that originated in the land of Edom and Moab, not Egypt. The problem with this speculation of Redford’s is that there is zero artefactual corroboration of this claim. There is nothing of material culture to support this speculation of Redford’s. It is an argument from archaeological silence.

Regarding the speculation that “Yahweh” is a place name, it could be conjectured that a city, town, or geographical area called “Yahweh” is still lying unexcavated in the ground. But there is more to the equation here than simply that there is no artefactual evidence for this. More pointedly, as already noted, the grammar of the phrase “land of the nomads of Yahweh” lacks the usual Egyptian place name determinative to indicate that “Yahweh” is a land or city or town. (A “determinative” is a grammatical sign lacking any phonetic value, similar to the way a question mark “?” has no phonetic value but determines the nature of the preceding statement as a question, and the Yahweh inscription at Soleb lacks this place name determinative.)

This lack of a place name determinative is a very difficult-to-explain omission if, in fact, Pharaoh Amenhotep III’s purpose was to identify an established place where these nomads roamed, rather than a random place where these nomads just happened to be at the time he claimed he subdued them.

The logic of the assertion does not hold up when you consider the inscription itself. On the assumption that ‘”YHWH” is a place name, the inscription would read “the land of the nomads of the land Yahweh.” If “YHWH” is a land, why not simply state “the nomads of (the place named) Yahweh?” The inscription itself distinguishes “land” from the distinct referent “Yahweh.”

Redford’s speculation that the Israelites originated in Edom or Moab is based wholly on the fact that other “shasu” (nomads) mentioned, whom Amenhotep III claims to have conquered, include sites in Edom and Moab. This is an impotent argument considering the grammatical nature of the statement and considering the proximity of Edom to Canaan. Canaan and Edom are the same general area. Consulting a map of ancient Edom and Canaan shows a large common border between the two.

We know for certain that “YHWH” is the personal name of God in Hebrew in the Scriptures. We have no evidence whatsoever that YHWH is a place name. All that can be said is that if there is a place that was called “YHWH,” then that place name is identical to the name of the Hebrew God that we know of for certain and which we find inscribed on the Soleb Temple. If there was a place named “YHWH” in Edom, it becomes all the more difficult to explain why there is no place name determinative in the inscription to avoid confusion.

In an online article regarding the Soleb Yahweh inscription, archaeologist Titus Kennedy comments:

The bound prisoner motif also implies that these SAsw nomads of yhwA were an alleged ‘conquered’ or ‘subdued’ people. As discussed previously, there is no land determinative, and therefore yhwA is probably a personal name, not a place name, nor is there a nTr ‘god’ sign or honorific transposition, indicating that yhwA was not a deity worshipped in Egypt. (from “The Land of the š3sw (Nomads) of yhw3 at Soleb,” 2019, in Dotawo, A Journal of Nubian Studies)

Evaluating Redford

Credit must be given where credit is due. Redford is a sophisticated propagandist. I must say I have a certain admiration of Redford in this regard, having read his treatment of this subject. Redford certainly swings his partisan bat for his team.

Let me supply an example of this subtle subversion. On page 272 of his book, Egypt, Canaan and Israel in Ancient Times, Redford renders the Yahweh inscription as “Yhw (in) the land of the Shasu.” Redford’s rendering here is a distortion of the message of the inscription on three fronts.

First, note well that Redford renders the Egyptian word for Yahweh with three letters — in quotation marks, no less. This is a subtle inference that what we have here may not be the Tetragrammaton even though Redford has already admitted that it is the Tetragrammaton. Redford, as a competent scholar, knows very well that the Egyptian script here, which is phonetic in nature, consists of four characters, as I noted above.

There is no doubt whatsoever that the pronunciation here precisely yields the name, “Yahweh,” a fact which Redford concedes. He even acknowledges that Yahweh is the name of the God of these nomads. Yet he slips in this subtle distortion which conveys the impression to his readers that maybe this is not the Tetragrammaton after all, but some other designation. This appears to me to be equivocation on Redford’s part of a most strategic nature. This is partisan scholarship, the attempt to scuttle the blunt force of the significance of the empirical, material remains of the past.

To be generous, the best that can be said of it is that this characterization of Redford reflects his inherent confusion about this information.

As Titus Kennedy comments in his article mentions above:

Therefore, the correct transcription of this hieroglyphic phrase on Column IV at the Soleb temple is tA SAsw yhwA. Since the word order infers that the construct is being used, the phrase translates as the ‘land of the nomads of yhwA.’ This appears to be equivalent to the deity name Yhwh known from West Semitic texts…

The above criteria demonstrate that the translation should be the ‘land of the nomads of Yahweh,’ not ‘Yahweh in the land of the nomads,’ which does not follow grammatically or in the context of the other SAsw groups associated with names in the Soleb inscriptions.

Secondly, by rendering “land of the nomads of Yahweh” as “Yhw (in) the land of the Shasu,” Redford disassociates the nomads from Yahweh and connects these “shasu”/nomads more intimately with the land. If that is what Redford wants to assert, that is his prerogative. Let him make his argument. But that is not the sense of the inscription. He cannot derive his argument from the inscription by itself.

Thirdly, note that Redford capitalizes “shasu” as “Shasu,” thus implying that “shasu” designates the title of a distinct people group — as in “Germans,” “Russians,” or “Canadians.” This serves to suggest that the inscription is referring to a people group distinct from the Israelites. Redford does not elaborate on this in his book but the logic of the designation suggests this possibility.

So what do we have here in Redford’s assertions?

We have the claim, with no corroboration from material culture, that the Hebrews, as a distinct ethnic group, originated out of Edom/Moab instead of with a migration from Egypt. We also have (what appears to me) to be a deliberate attempt to blunt the force of the significance of the name of God, Yahweh, from a non-biblical source. That source being no less than Amenhotep III, the exalted Pharaoh of Egypt himself.

I find both the empirical evidence and the secular scholars’ handling of it utterly amazing. In Donald B. Redford’s writings, we have the acknowledgment of a secular scholar, hostile to biblical faith, of the existence of the worshippers of Yahweh at around 1400 BC. A group whom Redford acknowledges would soon afterward become the nation of Israel.

The fact alone distinguishes these nomads from the Edomites and Moabites. That is, we do not have Edomite or Moabite imperialism mounting incursions into and attempting hegemony over Canaan, but a different and distinct people group).

This pushes the existence of the Hebrews, the Israelites, specifically the descendants of Abraham and Isaac and Jacob, hundreds of years earlier than what most secular scholars are willing to concede, to a time consistent with biblical chronology. I am certain that it was not Redford’s intent to validate biblical chronology, but that is, nevertheless, the result.

Therefore, I take it as an established fact that in the inscription on the Temple in Soleb, we have the earliest extant testimony of the name of God, Yahweh, and strong evidence for the existence of the Hebrews, around the time of 1400 BC, as a distinct people group, who were the worshippers of Yahweh, which was shortly afterward to become the nation of Israel.

The Timing of the Inscription

Let us step back for a wider view of the biblical chronological context of the Soleb Yahweh inscription. Some have suggested 1408 BC as the date of the inscriptions, some a little later around 1385 BC. Based upon biblical chronology (1 Kings 6:1; Judges 11:26), which puts the date of the exodus at 1446 BC, the Soleb inscriptions were made either during the time of the Hebrews’ wilderness wanderings before entering Canaan, during the time of Joshua’s military campaigns in Canaan, or shortly after Joshua in the early days of the Judges. Historically speaking, in any of these possible chronological scenarios, the inscriptions were made a short time after the Exodus in 1446 BC.

According to Exodus 3, God revealed his personal name of Yahweh to Moses for the first time shortly before the ten judgments on Egypt and the Exodus. Exactly how long the period of the ten judgments lasted is a matter of conjecture. Scripture does not specify the amount of time. In my opinion, the time frame of the ten judgments upon Egypt could not be more than a few years at most and probably less than that. The first confrontation of Moses with Pharaoh was probably no earlier than 1450 BC.

Is it not more than coincidence that the name “Yahweh” appears in the historical record for the first time just a few decades after the biblical date of Moses’ encounter with Yahweh? Why do we not find “Yahweh” 100 or 200 years earlier? Secular scholars will, of course, dismiss this as mere coincidence or blame it on the meager archaeological remains of the ancient world. But this is consistent with what we should expect if, in fact, the biblical account and chronology are true.

We will continue this series in Part 4: The El Amarna Letters

Online resources about the Soleb inscription:

Joel Kramer: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pGEOZ5YI22M

Associates for Biblical Research: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yXIo5Cp7_jc