Captivated by the wonder of the rows upon rows of colorful minerals, I enjoyed slowly looking over each one. It was like slowly eating a favorite dessert, savoring one bite at a time. After several days of busily going about on “sensory overload”, trying to process all the activity, new people, and information, it was nice to have a few uninterrupted minutes just to appreciate the minerals that my paleontology-focused group had a tendency to overlook. Here at the annual mineral, gem, and fossil show in Tucsan, Arizona, there were more minerals than I had seen anywhere else before.

It’s important to understand the difference between a mineral and a rock. A rock can be a bunch of minerals clustered together, like granite, which includes three minerals (read more about granite here). However, a mineral is more exclusive, as each one has a specific chemical composition. In its most common form, the mineral pyrite, familiarly known as “fool’s gold”, is iron sulfide (The chemical formula is FeS2). That special chemical identity gives each mineral certain ways that it can be recognized. Patterns in the way crystals of each mineral form and how they break often give away their identity pretty quickly to a trained eye. Some minerals fizz when you put vinegar on them, reacting to the acid. The things that tell us which mineral is which relates back to their chemical formulas.

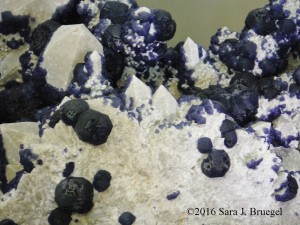

Thinking back on my first college geology class, the minerals I saw in Tucson were so much more diverse than the ones in my lab tray I had learned to identify. One of the most memorable minerals I saw looked exactly like juicy blueberries within peaks of a delicious cream. Odd as they looked, they were made of quartz and fluorite, which were two of the minerals we studied pretty seriously in that class. Quartz is a common mineral, and fluorite, though more rare, is very collectible. Both of these minerals can be seen in a number of different colors and forms. Blue fluorite like the “blueberries” I saw is one of the more rare colors. The blue color comes from trace amounts of the chemical yttrium inside the fluorite.

Fluorite is where we get fluorine, which is a common ingredient in toothpaste and drinking water, and is used in a number of other places. It’s thought of as a fairly soft mineral. We use the Mohs’ Scale of Hardness to compare how hard or soft minerals are. The hardest mineral, diamonds, are a 10 on the Mohs’ Scale, while gypsum (used in the sheetrock walls of houses – more about gypsum here) is a 2 on the Mohs’ Scale. Fluorite is about a 4 on the Mohs’ Scale. Since both fluorite and quartz can come in purple colors, one way you can tell the difference is by testing how hard the mineral is. Since fluorite is a 4 on the Mohs’ Scale, it’s soft enough to be scratched by a metal nail, but quartz, being a much harder 7 on the Mohs’ Scale, cannot be scratched with a nail. If it keeps the scratch, you know you have fluorite and if it doesn’t, you know you have quartz or something else harder.

Just as we can test minerals to tell what their true identity is, it’s important that we examine ourselves and test our hearts to make sure our identity is right with Christ. Second Corinthians 13:5-6 says, “Examine yourselves as to whether you are in the faith. Test yourselves. Do you not know yourselves, that Jesus Christ is in you? – unless indeed you are disqualified. But I trust that you will know that we are not disqualified”. Next week, we will talk more about minerals and how to identify them.

Copyright Sara J. Bruegel, May 2016

References:

Hobart King. Fluorite (also known as Fluorspar). Minerals. Geology.com. Last accessed 5-27-16 http://geology.com/minerals/fluorite.shtml