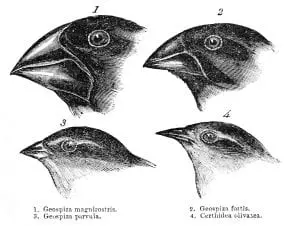

[Originally published as Fate of Darwin’s Finches]

The fate of Charles Darwin’s finches is a fascinating saga.

With their origins far from England, in the equatorial Pacific Ocean more than 800 miles off the west coast of Ecuador, the finches Darwin captured on the Galápagos Islands, except for one tag, are now missing. As one of the most controversial birds in modern history, the fate of Darwin’s finches belies their current iconic status.

Reaching the Galápagos Islands on September 15, 1835, more than four years after leaving England, the HMS Beagle started preparations to set sail from the island just five weeks later. Darwin had collected many different types of specimens during that time, some weighing up to 500 pounds each. Although typically an avid collector and note-taker, Darwin surprisingly did not record the number of finches collected nor the number loaded onto the ship.

Notebook

In his working notebook while on the islands, Darwin’s only faint reference to a finch is the phrase “Gross-Beakes.” Most of the birds collected were the work of his servant, Syms Covington. Darwin’s interest in the finches, however, seems surprisingly ambivalent.

By mid-October 1835, with Captain Robert FitzRoy‘s surveying goals nearing completion and anxious to set sail, the specimens Darwin and Covington collected on the islands were loaded into the ship. Eventually, thirty-one Galápagos finches landed on the shores of England.

Geological Society

Within a month of returning from the five-year voyage to England in 1836, Darwin presented some of the new collection at the January meeting of the Geological Society of London. Following the meeting, British ornithologist John Gould studied the birds in more detail.

Later that month, Gould concluded that the birds were “blackbirds, gross-bills, and finches.” Gould reported further that the “series of ground finches which are so peculiar” as to form “an entirely new group, containing 12 species.”

Gould’s report, inferring the evolution of “an entirely new group, containing 12 species,” received prominent news attention fueling the emergence of the Darwin finch saga.

Later that year, however, Darwin donated his Galapagos bird collection to the Zoological Society of London. Apparently, Darwin had no immediate plans to study the collection further.

Finches by Island

Two years later, in 1839, when Darwin published the first edition of the Journal of Researches, also known as the Voyage of the Beagle, Darwin never mentioned the Galápagos finches. The birds as evidence for evolution were seemingly unnoticed, at least at the time.

With Gould’s support, however, and emerging excitement over his collection, Darwin seemed to gain a newfound interest in the birds. Darwin began arranging the finches by island using his notes and memory. As Darwin Online, the world’s largest and most widely used resource on Charles Darwin, explains:

Certain of Darwin’s attempts to reconstruct the island localities of his own specimens involved a bit of guesswork, and errors inevitably crept in.

Curiously, a decade after returning to England, in 1845 in the second edition of the Journal of Researches, Darwin mentions the finches on the Galapagos Islands seventeen times, but concedes:

Unfortunately, most of the specimens of the finch tribe were mingled together.

When the Zoological Society decided to close operations in 1855, an offer was presented to the British Museum to purchase the collection. In the transaction, however, only nineteen of Darwin’s original finches were relocated to the British Museum.

The Origin of Species

More than two decades after returning to England, in the first edition of The Origin of Species in 1859, while Darwin mentioned the “Galápagos” seventeen times, “finches” are only mentioned twice. Tellingly important, Darwin never used “Galápagos” and “finches” together in the same sentence or even in the same paragraph.

Darwin did write one paragraph in The Origin of Species to describe what he called “mocking-thrush.” However, these are considered to be the mocking birds referred to as “Gross-Beakes“ in his Galapagos notebook, not finches. The nearest reference to finches in The Origin of Species is in the following sentence:

In the Galapagos Archipelago… there are three closely-allied species of mocking-thrush, each confined to its own island.

Between the voyage and the book’s publication, however, more than two decades had elapsed. Asserting that “each was confined to its own island,” can only be deemed “guesswork.”

Evaluating the Evidence

While the whereabouts of the birds are unknown today, the saga speaks volumes for the perceived importance of the birds during Darwin’s lifetime—they weren’t. According to Frank Sulloway of the University of California, Berkeley, only one of the original finch tags is even known to still be in existence today.

While the whereabouts of the birds are unknown today, the saga speaks volumes for the perceived importance of the birds during Darwin’s lifetime—they weren’t. According to Frank Sulloway of the University of California, Berkeley, only one of the original finch tags is even known to still be in existence today.

Only Gould’s vague evidence, at best, supports the once-popular argument that the Galapagos finches provided Darwin scientific evidence for his theory. Importantly, though, Darwin never argued that the finches delivered supporting evidence for his theory. The iconic status of the Darwin finch saga, ironically, cannot be attributed to Darwin. As Sulloway explains:

Darwin was increasingly given credit after 1947 for finches he never saw and for observations and insights about them he never made.

Niles Eldredge, the curator for the American Museum of Natural History, notes that interest in the finches “came long after Darwin sailed away from the Galápagos [in 1835], having paid these birds hardly any heed.” Erin Blakemore, writing for the Smithsonian Magazine, points out:

The story that those birds inspired the theory of evolution has long been doubted.

While the Museum of Zoology at the University of Cambridge has the largest inventory of specimens collected by Darwin, yet there is not a single Darwin finch in their collection.

The British Museum has four mockingbird specimens thought to have been collected by Darwin on the Galápagos Islands; however, the final fate of the nineteen specimens they acquired in 1855 is unknown. Only the one identification label, once on a finch, remains as evidence today.

Extinction

By the end of the 21st century, the Galapagos Island finches may become better-known as an example of extinction rather than evolution. Blakemore explains in a Smithsonian article entitled “Charles Darwin’s Famous Finches Could Be Extinct in Half a Century,” noting that

The finches on the Galapagos Islands are suffering from a parasitic fly introduced to the islands by humans.

This parasitic fly, introduced to the islands in the 1960s, is known as Philornis downsi. Darwin’s finches, however, would not be the first to face extinction on the Galapagos Islands due to this fly.

A bird species, the vermilion flycatcher (Pyrocephalus dubious), which once lived on the easternmost island of the Galapagos, has not been seen since 1987. Numerous searches have since confirmed their extinction.

While the reason for the flycatcher extinction is not definitively known, this same parasitic fly is now infesting the nests of the Galapagos finches. Scientists are exploring similarities between the flycatcher extinction and the possible extinction of the Galapagos finches. Fly Infestations denude newborn finches with fatal consequences.

“Extinction and natural selection go hand in hand,” Darwin argued—but not evolution. The once iconic status of the Galapagos finches as evidence for evolution increasingly resembles the iconic status of the Piltdown man. The fascinating finch saga only intensifies the Darwin dilemma.

Genesis

After more than a century of research on the Galapagos finches, interestingly, Darwin’s ambivalence towards the Galapagos finches has stood the test of time. Evidence for evolution, though, has not.

Only theories compatible with the Genesis account have proven to be valid scientifically. An example includes the theory of species developed by the Swedish botanist, physician, and zoologist, Carolus Linnaeus’ (1707-1778). As Linnaeus explains:

All the species recognized by Botanists came forth from the Almighty Creator’s hand, and the number of these is now and always will be exactly the same.

Evolution exists only as a theory, not as a valid scientific law of nature.

What arrant nonsense. The theory of evolution doesn’t just depend on finches! Linnaeus might have had a different view if he had read the Origin of the Species but he died long before Darwin’s insight. In what way can a book written two thousand years ago by a group of nomads be considered valid scientifically?

Appreciate your comments.

True – Darwin’s theory of evolution does not depend just on the Galapagos finch beak sizes. The validity of his theory was contingent on finding “innumerable” transitional links. Darwin claimed that his theory was “one long argument,” not a valid scientific theory. In fact, Darwin wrote that his theory was actually “beyond the bounds of science.”

Presuming that Linnaeus would have responded differently after reading the Origin of Species might be considered “arrant nonsense,” too?

Interestingly enough, what you call a “group of nomads” is not true. The biblical account was actually written by 44 different writers over a period of 1500 years – they were not exactly a “group of nomads.” Only a few of the writers ever knew the other writers. A number of the presumed “nomads” were actually rulers of some of the most powerful groups of people, at the time.

Please post a list of some of the things in the biblical account you think are scientifically invalid?