In the month of March 1496, King Henry VII of England granted the Italian explorer John Cabot the authority to sail all parts of the eastern, western and northern seas, “to discover and investigate whatsoever islands, countries, regions or provinces…in whatsoever part of the world placed, which before this time were unknown to all Christians.”[1] What Cabot discovered and would later claim as English land was the east coast of Newfoundland; it was the beginning of North American colonization.[2]

As the years passed the new world become colonized, relationships were established with the First Nations people, and land was divided and allotted to the provinces. The founder of New France, Samuel de Champlain, said that upon observing the settled tribes of the new world without the Christian faith or law, living without God, he concluded that “I should be committing a grave sin if I did not make it my business to devise some means of bringing them to the knowledge of God.”[3] By this he meant the proclamation of the gospel of Christ, for which countless missionaries have given their lives in order that others might learn and receive the Christian faith.[4] It was their dream to see the new land reflect the universal reign of Jesus Christ.

When the time came for the unification of the British colonies, there was extensive debate about the term that would be used to describe our country. The Father of Confederation who became Canada’s first Prime Minister, Sir John A. MacDonald, had proposed the title “Kingdom of Canada,” but the connotations of such a title were considered too provocative for the United States. The protestant Sir Samuel L. Tilley, Premier of New Brunswick, proposed a title derived from his daily Bible readings, “The Dominion of Canada.” The title, inspired by Psalm 72:8, referring to the universal reign and rule of Christ, was adopted and reported to Queen Victoria of Britain, signed by MacDonald, in which he wrote that “the name was a tribute to the principles they earnestly desired to uphold.”[5] The implications of the title were theologically significant, given its eschatological and cultural context, and it was approved by the thirty-three Fathers of Confederation.

This was the vision for early Canada, a nation that acknowledged Jesus Christ as King and Saviour, subject to His law, under His dominion, and as sovereign Lord God over our nation and all the earth. There is a bronze plaque in the Legislative Chamber of Charlottetown, PEI, which states: “Providence being their guide, they built better than they knew.”[6]

The confederation of Canada would not have been possible if it were not for the churches of Canada, which, although not directly involved with the process, played a vital role in fostering an attitude of receptiveness toward a new nation.[7] In fact, nation-building was “one of the central concerns of Canadian Protestantism since Confederation,” with the church stressing personal salvation for the people of Canada, and the redemption of society at large.[8] As a unified church, they believed that Canada ought to be “fashioned into ‘God’s dominion’… from sea to sea,” and from there its attention shifted towards “what constituted a righteous nation.”[9]

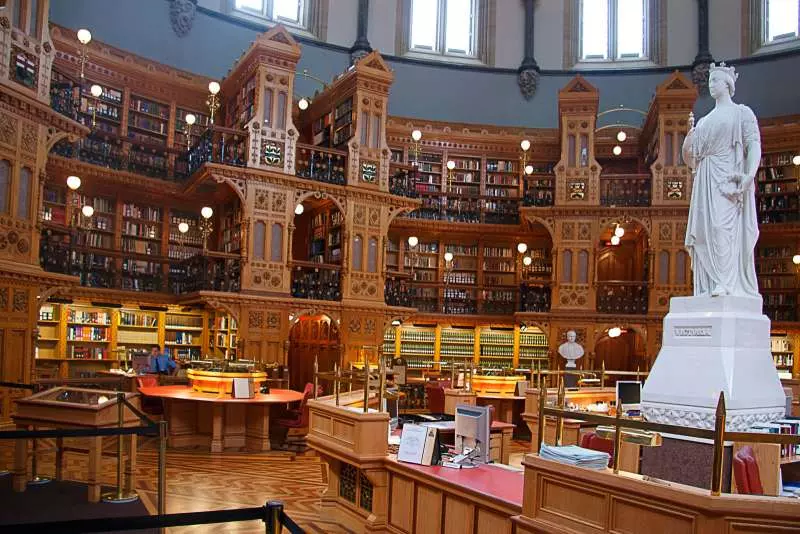

Not long after confederation, formal denominational records were publicly released from the Presbyterian Church, the Methodist Church, and others, detailing their beginnings in Canada, and their implied belief that “the [Christian] faith [had been] firmly planted in Canada.”[10] The biblical gospel played a “central role in the development of Canada,” and where the later “secular political or economic forces and institutions” failed in the nation-building process, it was the Christian convictions of the people that helped keep the nation on a broadly Christian track.[11] The church of Canada, diverse as it was, “viewed themselves as the conscience of the state,” and the leaders of our nation, the politicians, “were expected to judge all matters by Judaeo-Christian values.”[12] The rich Christian heritage of Canada could fill (and has) volumes of books[13] and is etched throughout Ottawa’s Parliament buildings in the form of engraved Bible passages.[14]

Repainting Canada as Islamic?

With Canada’s Christian heritage so unmistakably attested to, what could have led Prime Minister Justin Trudeau to state that the underlying “teachings of Ramadan are the values of empathy, generosity and discipline – principles upon which Canada is founded”?[15] Ramadan is the ninth lunar month in the Islamic calendar,[16] a time for Muslims to fast (Surah 2:183) from sunrise to sunset, and to read the Qur’an introspectively.[17] It is the commemoration of Muhammad’s reception of the Qur’an as revelation from Allah, and according to Trudeau:

During the holy month of Ramadan, Muslims in Canada and around the world fast and engage in deep spiritual reflection, recommit to a life guided by compassion and charity, and foster spiritual renewal of themselves and their communities.[18]

This is true as far as it goes, though that isn’t very far. Ramadan is one of five pillars of Islam, a necessary component for Muslim living which also includes the confession of faith, five daily prayers, almsgiving and the Hajj (pilgrimage to Mecca). The purpose of fasting during Ramadan is the improvement of “their moral characters and provides an opportunity for spiritual renewal.”[19]However this religious observance must be understood within its Islamic context. Observing Ramadan is a demonstration of gratitude to Allah for the revelation of the Qur’an, and for the sending of his final prophet.[20] If Trudeau is willing to endorse Ramadan, he must be willing to endorse the text from which the observation is mandated (Surah 2:185). And given the unimpeachable status of Muhammad in Islam, the text of the Qur’an, as well as the prophet’s teaching in both speech and exemplified behaviour, are inseparable. If we are referring to “compassion and charity” as advocated in Ramadan, then are we not to reconcile those values with the Qur’anic text and the life of Muhammad?

Indeed, we must consider how Muhammad treated the pre-Islamic Arabs, who he identified as idolaters. Muslim apologists generally cite Surah 2:256, which reads “There is no coercion in religion. Sound judgment has become clear from error. So whosoever disavows false deities and believes in God has grasped the most unfailing handhold, which never breaks.”[21] There are Muslims who sincerely believe this to literally mean “no coercion,” that is, respect for all religions, however there are widely varying positions on this doctrine within Islam. Alternatively, Qur’anic exegesis maintains that:

The Arabs were in fact forced to abandon idol worship… the import of this verse is not absolute, since the Prophet, in his campaign and ultimate victory against the idolatrous Arabs, did not give them the option of remaining idolaters or paying the jizyah [tax].[22]

It is a legitimate question to ask how the life and teachings of Muhammad compare to the ministry of Jesus, the centerpiece of the Christian faith – the faith which demonstrably played a critical role in the founding of our nation. Where the Christians and the Jews were permitted to co-exist, while required to pay the jizyah (tax) for their refusal to convert to Islam, the pagan Arabs were granted no such concession, and were utterly destroyed, cleansed from the holy sites of Islam. We see no such compulsion in the life and teachings of Christ, instead we find:

But I say to you, love your enemies and pray for those who persecute you, so that you may be sons of your Father who is in heaven. For he makes his sun rise on the evil and on the good, and sends rain on the just and on the unjust. For if you love those who love you, what reward do you have? Do not even the tax collectors do the same? (Matt. 5:44-46).

Which worldview embodies compassion and charity? The religion of Islam and its Qur’anic teachings, which supposedly exemplify “diversity of cultures, languages and religions” as Trudeau[23] and Obama believe?[24] Or the Christian worldview, where our Lord and Christ, who has every right and all power to condemn us for our sin, instead bestows his grace to men and women of all nations? The Qur’anic teachings are antithetical to the Christian worldview; they fail to make sense of empathy, compassion and human dignity when man is created to be nothing more than Allah’s slave (for this is what it means to be a true servant of Allah).[25] Moreover, on what basis can compassion, charity or human dignity be defined? The doctrine of Allah asserts that he cannot even be known because he is so other that he becomes unintelligible to the human mind. As the commentator Fadl Allah states, “The mental faculty cannot reach Him in His elusive and hidden mystery.”[26]Christianity, however, boldly proclaims that man is created in the image of God, and on that basis can human dignity be understood. We bear the value of the One whose image we bear, and in bearing His image we are able to enter into relationship with Him because He is intelligible to us and has revealed Himself to us.

Trudeau’s statements are an affront to Canada’s Christian heritage, utterly ignorant of the role of the gospel in Canada’s early years; but they reflect the character of our contemporary culture. He speaks for a nation that has all but forgotten the Christian vision upon which our country was founded, and which is gullible enough to believe that Canada was a pluralistic nation, or even in some form influenced by Islamic teaching. In an age where many are willing to sacrifice truth on the altar of tolerance, we must remain firm in our confession of faith and proclaim the exclusivity of Christ and the truth of the gospel over all falsehoods; this is truly part of our Canadian heritage:

After Confederation…unified, affluent Protestant churches in Canada carried the Gospel to regions Caesar never knew – China, Japan, Formosa and India. By the turn of the century Canadian Protestant churches could count over four hundred missionary preachers, teachers, doctors, dentists, nurses, agriculturalists, etc. in foreign fields.[27]

May we take up our calling to be heralds of the good news of Christ, proclaiming the gospel in life and speech, living our faith in the public square and applying it to all spheres of life. We the redeemed, having been renewed in Christ, are representatives and ambassadors of God’s glory, demonstrating the love and goodness of God through all our cultural endeavours.

Originally posted at the Ezra Institute for Contemporary Christianity website.

[1] Patent granted by King Henry VII to John Cabot, Heritage Newfoundland & Labrador, accessed February 25, 2016, http://www.heritage.nf.ca/articles/exploration/1496-cabot-patent.php.

[2] R. Douglas Francis, Richard Jones, and Donald B. Smith, eds., Origins: Canadian History to Confederation, sixth edition (Toronto: Nelson Education, 2009), 29.

[3] Raymonde Litalien and Denis Vaugeois, eds., Champlain: The Birth of French America (Montreal & Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2004), 198.

[4] See Michael D. Clarke, ed., Canada: Portraits of Faith (Medicine Hat, AB: Home School Legal Defense Association of Canada, 2001).

[5] Michael Clarke, Canada: Portraits of the Faith (Canada: Reel to Real, 1998), 60.

[6] “Canada Day,” Governor General of Canada, last modified September 5, 2012, accessed August 28, 2015, http://archive.gg.ca/media/doc.asp?lang=e&DocID=1211

[7] John Webster Grant, The Church in the Canadian Era, updated and expanded. (Vancouver: Regent College Publishing, 1988), 24.

[8] Robert A. Wright, “The Canadian Protestant Tradition 1914-1945,” in The Canadian Protestant Experience 1760-1990, ed. George A. Rawlyk (Montreal & Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1990), 150-151.

[9] Grant, The Church in the Canadian Era, 19.

[10] Ibid, 43.

[11] John S. Moir, Christianity in Canada: Historical Essays, ed. Paul Laverdure (Yorkton, SK.: Redeemer’s Voice Press, 2002), 1.

[12] Ibid.

[13] As just a beginning, see for example John W. Grant, The Church in the Canadian era, updated and expanded edition (Vancouver: Regent College Publishing, 1988); John S. Moir, Christianity in Canada: historical essays, ed. Paul Laverdue (Yorkton, SK.: Redeemer’s Voice Press, 2002); George A. Rawlyk, ed., The Canadian Protestant Experience 1760-1990 (Montreal & Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1990).

[14] See Steven Martins, “The Peace Tower, Parliament, and Christian Canada,”Ezra Institute for Contemporary Christianity, August 15, 2015, accessed March 4, 2016, http://www.ezrainstitute.ca/resource-library/articles/the-peace-tower-parliament-and-christian-canada.

[15] Liberal Party of Canada, “Statement by Liberal party of Canada Leader Justin Trudeau on Ramadan,” Liberal Party of Canada, July 9, 2013, accessed February 25, 2016, http://www.liberal.ca/statement-liberal-party-canada-leader-justin-trudeau-ramadan/.

[16] Rick Richter, Comparing the Qur’an and the Bible: What they really say about Jesus, Jihad, and more (Grand Rapids: Baker Books, 2011), 155.

[17] Egun Mehmet Caner and Fetthi Emir Caner, Unveiling Islam (Grand Rapids: Kregel, 2002), 127.

[18] Liberal Party of Canada, “Statement by Liberal party of Canada Leader Justin Trudeau on Ramadan.”

[19] Islamic Foundation, “Month of Ramadan,” Islamic Foundation of Toronto, 2016, accessed March 4, 2016, http://www.islamicfoundation.ca/ramadan.aspx.

[20] Shahul Hameed, “The prophet in Ramadan – the religion of Islam,” The Religion of Islam, 2006, accessed March 4, 2016, http://www.islamreligion.com/articles/1708/prophet-in-ramadan/.

[21] Seyyed Hossein Nasr et. al., eds., The Study Quran: A New Translation and Commentary (New York: Harper Collins, 2015), 111-112.

[22] Ibid, 112.

[23] Liberal Party of Canada, “Statement by Liberal party of Canada Leader Justin Trudeau on Ramadan.”

[24] The White House, “The President Speaks at the Islamic Society of Baltimore,” posted February 3, 2016, accessed February 25, 2016, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LRRVdVqAjdw.

[25] “Question 5: Being Allah’s servant,” Al-Islam, accessed March 4, 2016, http://www.al-islam.org/faith-and-reason-ayatullah-mahdi-hadavi-tehrani/question-5-being-allah-s-servant.

[26] Cited in Feras Hamza, Sajjad Rizvi, and Farhana Mayer, eds., An Anthology of Qur’anic Commentaries, volume 1 (London: Oxford University Press, 2008), 492.

[27] Moir, Christianity in Canada, 3.