Photo credit: David Mikkelson, 2016

I could feel the bright sunlight beams gently warming my back as they slowly made their way around the nice shade. Sitting up tall on the ground, I traded my chisel and hammer for a water bottle to give my eyes a quick break from the careful work around a delicate fossil. Looking across at my fellow-diggers, I asked how progress was going. They were finding more fossils . . . one that could be pretty big and complete, going deeper into the rock below, another that looked very interesting. Brows furrowed. Oh dear: another fossil. That could be discouraging to find on a dinosaur dig, right? We all laughed. In general, people would think that finding another cool fossil on a dinosaur dig is very good and exciting – and it really is exciting! After all, discovering and digging fossils is the point of a paleontological dig. But, working in Colorado, the fossils are so close together and usually all jumbled up, making it hard to properly excavate one fossil without running into or endangering other fossils.

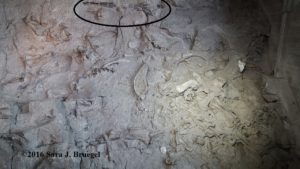

Digging up fossils in the Morrison Formation in Colorado is a little like playing a game of “Pick-up Sticks”, but using huge, fossilized leg or shoulder bones from a dinosaur instead of thin, plastic sticks. Just as the sticks can get tangled together and mixed up, making it challenging to remove one of the sticks without disturbing the others, getting the desired fossils out carefully can be a challenging puzzle. In the same rock formation, but west of where I was digging, some historic dinosaur finds were made near Vernal, Utah. Of course, the paleontologists digging there encountered the same problems I did – the rich mines of bone upon bone made it practically impossible to take out some of the fossils. They decided to go a different route with these fossils. Instead of taking them entirely out of the rock formation, they built a 150-foot-long building around the steeply tilted layer, partially exposed fossils and all, making them into a museum of their own – known today as the Quarry Exhibit Hall of Dinosaur National Monument.

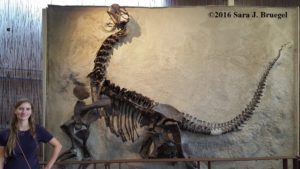

At Dinosaur National Monument and where I was digging in the Morrison formation, you can find many dis-articulated fossils, with bones separated and all mixed up with bones from different dinosaurs. But, at the same time, there are some articulated dinosaurs, that have either sections of bone or most of the animal in the right order. I could clearly see this looking at the wall of bones at Dinosaur National Monument – there was one Camarasaurus with its neck clearly bent backwards and most bones in their rightful places. While there have been several old-earth models trying to explain how these fossils came to be preserved as we see them today, there are a number of problems with each of them. The model currently taught at the quarry exhibit essentially says that these dinosaurs died beside a river, and were periodically buried by normal flooding along the banks.

But, taking a closer look at these fossils and the rock in which we find them reveals some big problems with this model and other models. Spread across several states, the sandstone from this section of the Morrison formation includes more than 4,000 cubic miles of volcanic ash and rock. These are not the types of pebbles and sand you would expect to find along a river. Furthermore, there aren’t any nearby volcanoes that this ash and rock would have come from in the currently taught model. If the dinosaurs were buried where they lived (like according to the river model), we would expect to find plants buried with them, but only a few petrified tree trunks are there. Preserving some articulated dinosaurs mixed with disarticulated fossils would also be difficult to explain in the local-flooding river model.

Instead of slow burial along a river, what if we use the Biblical global flood a model to explain how these dinosaurs were buried? Volcanoes would have been going off underwater (the “fountains of the great deep” in Genesis 7), providing the ash and volcanic rock buried with the fossils. Dinosaurs would have been swept away, swirled with logs and other things, separating some of their bones and carrying them away from their normal environment. Other dinosaurs would have tried to outrun the flood before finally being buried with the scattered bones of their friends. Rather than merely animals living and dying by a nice river, these dinosaurs are a monument to the catastrophic, global flood mentioned in the Bible. It’s a monument to the justice of God met together with His preserving mercy, using even His judgement to make some spectacularly beautiful things – including the rock formations and fossils we see today.

Copyright Sara J. Bruegel, September 2016

References:

- Personal visit to Dinosaur National Monument Quarry Exhibit Hall. Vernal, Utah. August 2016

- Answers in Genesis. July 31, 2008. Wonders of Geology: Dinosaur National Monument in Utah. Last accessed 9-30-16

https://answersingenesis.org/fossils/dinosaur-national-monument-in-utah/ - William A. Hoesch and Steven A. Austin. 2004. Dinosaur National Monument: Jurassic Park Or Jurassic Jumble?. Acts & Facts 33 (4). Last accessed 9-30-16

http://www.icr.org/article/dinosaur-national-monument-park-or-jurassic-jumble